Comfort in My Retirement

President James K. Polk's "Mount Vernon"

Copyright © Summer 2013 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

Portrait of President James K. Polk at about age 50 by George P.A. Healy, 1846. To Polk, the long sittings were irksome, fatiguing, and “time unprofitably spent.”

They have been four years of incessant labour and anxiety and of great responsibility. I am heartily rejoiced that my term is so near its close. I will soon cease to be a servant and will become a sovereign. As a private citizen I will have no one but myself to serve, and will exercise a part of the sovereign power of my country. I am sure I will be happier in this condition than in the exalted station I now hold.”1 Thus the eleventh president, James Knox Polk, summed up his tenure in the White House. During his promised single term, he accomplished all of his major goals and many more minor ones by subscribing to a Herculean work ethic that often consisted of seventeen hours or more in his office each day, and just twenty-seven vacation days logged. Polk prided himself on having the ability to direct, down to the smallest detail, every aspect of the executive branch of government, sometimes to the chagrin of his subordinates. His secretary of state and future fifteenth President James Buchanan once lost a bet of a basket of champagne to the pedant president. Arguing over the format of a diplomatic letter, Polk bet Buchanan that he could not find a precedent for such wording in the archives of the State Department. After an exhaustive search, Buchanan sheepishly offered the president the bargained-for champagne, which Polk refused to accept, pleased enough that he had mastered his secretary in his own duties.2 Buchanan summed Polk up as “the most laborious man I have ever known.”3

Despite his intense focus on work, James K. Polk did allow himself one day out of each year to ponder his future. On November 2, his birthday, he would pause in reflection. At first contemplating the folly and finality of mankind, he would also look ahead with anticipation at what was surely to be a long retirement from public life, for he was the youngest man to hold the office to date. And as with all things, Polk had a plan.

Exterior of Polk Place in Nashville, Tennesee. The retirement home of President and Mrs. James K. Polk, it was demolished in 1901. The tomb, designed by William Strickland was then moved to the Tennessee Capitol grounds.

Because of his promised single term, Polk knew that retirement would begin for him at the age of fifty-three. Looking forward to a more relaxed life of refinement in their home state of Tennessee, James and Sarah Polk decided that their modest one-and-a-half story cottage in Columbia would neither befit their new lifestyle nor properly accommodate the social needs of a retired president. They had a model to follow. Polk’s first vacation day while president was a day-trip to visit George Washington’s Mount Vernon. He must have been impressed with the spacious home and grounds. He visited Washington’s gravesite, with the sarcophagus designed by architect William Strickland, and probably contemplated his own legacy. Polk wanted his own version of Mount Vernon, and he had the opportunity to make it happen in Nashville.

Grundy Place had been built between 1818 and 1820 by Senator Felix Grundy, former attorney general in President Martin Van Buren’s cabinet and the man who trained Polk in the law. Grundy died in 1840, and his heirs offered his house and sizable city lot for sale, just one block from the new Tennessee State Capitol then being erected by none other than William Strickland. Grundy Place was the grandest house in Nashville at the time it was built. The two-story, Palladian-style brick home was 74½ feet in width, featuring two parlors 27 feet square, separated by a 15 foot hallway. The other rooms were proportionally sized.4 It would certainly meet the needs of James and Sarah Polk nicely when retirement came in the spring of 1849. President Polk finalized the purchase of the house in 1847 at a cost of $6,000, and amid his busiest period as president, with a war in Mexico raging, he immediately began to redesign and update Polk Place in Nashville from his office in the White House.5

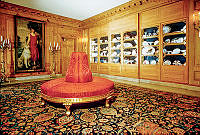

This previously unpublished photograph of the interior of Polk Place was taken near the time of Sarah Polk’s death in 1891. A number of furnishings depicted in this image, such as the mahogany coat rack, are now in the collection of the James K. Polk Ancestral Home.

James K. Polk Ancestral Home CollectionPolk contracted builder James M. Hughes to complete the substantial modifications to the house. First, Polk wanted to change the then old-fashioned Palladian-style house into the more popular Greek Revival. As per the new plans, round-topped windows were to be made rectangular, the roof flattened, and a great portico with fluted columns and Corinthian capitals added to the front facade. Just as work began, disaster struck. A gunpowder magazine in downtown Nashville was hit by lightning and exploded. The north and west walls of Polk Place were blown down and window frames were shattered.

President Polk saw opportunity from disaster. He would design Polk Place again, this time making it larger and detailed to his own specifications. He once again chose Hughes to undertake the work. The plan, as outlined by Polk with his wife’s input, was typical of the detail with which he undertook all projects. The description was so complete that Hughes agreed to the scope of work, including demolition “according to the plans given in President Polk’s letter of the 12th Feby 1848.”6 How did Polk manage? He explained to a friend, “You may think it strange that in the midst of my public engagements, that I can find time to write you so long a letter about my private affairs,—but you will remember that being a man of business habits, I can always find time to do, whatever is necessary to be done,—and certainly nothing is more necessary, than to provide for my comfort in my retirement,—and when I shall be in my declining years.”7 The work was to be completed by January 1, 1849, in plenty of time for the Polks’ arrival in April.

A mahogany coat rack, now in the collection of the James K. Polk Ancestral Home.

James K. Polk Ancestral Home CollectionWith construction well under way on Polk Place, the question facing the Polks was how to furnish a home much larger than their old Columbia residence. Experience was on their side. In 1845, the Polks were given a $14,000 congressional appropriation to refurbish the State Floor of the White House. Sarah Polk took charge of the project and with the help of friends like William Wilson Corcoran, transformed the shabby, well-worn White House into a showplace. Corcoran sometimes made trips to the New York store of Alexander Stewart. From there he made purchases of fine furniture, wallpaper, window treatments, and carpets for the President’s House, which were all approved by Mrs. Polk.8 No time was wasted in their endeavor. All was in place and unveiled to the public at a grand reception on New Year’s Day, 1846. In 1847 and 1848, Mrs. Polk simply repeated the process for Polk Place.

Although the Polks had been frequent visitors to Grundy Place for more than twenty years, they probably had not visited it since Felix Grundy’s death in 1840, and not at all since the explosion took place and the redesign began. Mrs. Polk decided it was necessary to make a visit before ordering decorative materials. On June 22, 1847, she departed Washington for Tennessee accompanied by her niece Joanna Rucker and a Mr. Russman, who would act in the capacity of personal attendant. Besides visiting family, her aims were to measure rooms and begin devising a plan to properly and elegantly outfit Polk Place.9 Upon her return to Washington on August 5, she put into motion an assembly line of merchants who came to the White House with swatches of materials and patterns for her to preview. She once again importuned her friend Corcoran to act as her agent in New York City, and she even ventured to the city once herself. The president recorded the trip in his diary on November 9, 1848: “At 6 O’Clock this morning Mrs. Polk left in the Eastern cars for New York. She was accompanied by my Private Secretary (Col. Walker) and our two nieces (Miss Rucker & Miss Hays) a man servant (Bowman) and a maid servant (Teresa). Her object in visiting New York was first to afford the young ladies an opportunity of seeing that City, but mainly to select some articles of furniture for our house, which is building at Nashville, Tennessee, and to have them shipped home via New Orleans.”10 Although receipts and records of purchases are scant, Sarah Polk likely bought furniture through Alexander Stewart’s store as she had done for the White House in 1845.

This previously unpublished photograph of the interior of Polk Place was taken near the time of Sarah Polk’s death in 1891.

James K. Polk Ancestral Home CollectionThis substantial collection of furnishings, which was to grace the halls of Polk Place for more than forty years and is now the centerpiece of the collection at the Polk historic site in Columbia, Tennessee, reflects the same elegant tastes and designs used for the White House redecoration. The Empire-style sofas and matching gentleman’s chairs feature rosewood frames, highly carved, with rich red velvet and silk upholstery. A set of thirty-three delicately carved side chairs was to ring the parlors for the many guests who would be coming to visit. Curtains were made of heavy silk damask in values of gold and red, and carpets were woven with geometric patterns and overlaid with runners of contrasting designs. The figurative but noncontrasting gray wallpapers were much like those installed in the White House.

As the planning for the redesign of Polk Place came to a close, so, too, did Polk’s presidency. Working right up to their departure from Washington, Polk marked the end of his term by writing, “I disposed of all the business on my table down to the minutest detail and at the close of the day left a clean table for my successor.”11 Accompanied by their nieces, the Polks boarded the train south. They took a circuitous route home to Nashville, moving down the Eastern seaboard, then inland through Georgia, thence by water to Mobile, Alabama, New Orleans, and up the Mississippi River, finally reaching Nashville on the Cumberland River. They had been feted all along the way in every city they passed, and their trip became a triumphal tour, neatly capping off a highly successful presidency. They anticipated moving directly into Polk Place, but found the construction still very much under way. Disappointed, they left their White House steward, Henry Bowman, who followed them from Washington, to oversee the final touches on Polk Place while they spent the next three weeks visiting friends and family in Columbia and Murfreesboro. Returning to Nashville on April 24, Polk recorded the day in his diary:

This center table featuring the Presidential Seal was presented to President Polk by the consul of Tunisia in 1849.

Detailing of the Presidential Seal in Scagliola (an imitation marble inlay) on a center table that was presented to President Polk.

"The work has not finished [on our house], but two or three rooms had been fitted so that we could occupy them. Numerous boxes of furniture, books, groceries, and other articles, forwarded from New York, New Orleans, and Columbia, Tenn., was piled up in the Halls and rooms, and the whole establishment, except two or three apartments, presented the appearance of great disorder and confusion. Our faithful steward, Henry Bowman, had in our absence to Columbia & Murfreesborough caused the carpets to be made and put down in some of the rooms and caused our furniture to be opened. Our servants had arrived from Columbia and were comfortably settled in the servant’s House. We thought it best to take possession of the house at once and superintend the arrangements necessary to put it in order. On this day therefore may be dated our first occupation of our new home in Nashville."12

Over the next month, the Polks, along with their servants, worked hard to turn Polk Place into a home. They filled the rooms with their furnishings new and old. The lack of color in the gray wallpaper was offset by the spectacular collection of decorative pieces the Polks purchased for Polk Place and acquired by gift during their presidential term. Polk admired the Hannibal and Minerva clocks purchased by President James Monroe for the White House and ordered similar figural clocks in gilt ormolu for the white marble mantels at Polk Place. A vast portrait of Hernán Cortés, the sixteenth-century Spanish conquistador, hung in the entrance hall, a reminder of Polk’s similar venture of conquest into the heart of Mexico. Sarah’s collection of fans could be seen; two in particular stood out. The “National Fan” was presented to her for use at her husband’s inauguration. The gilt paper held in place by bone stiles featured lithographic images of the first eleven presidents. Another fan with hand-painted paper on solid gold stiles was brought back from Mexico by General Gideon Pillow. A beautiful scagliola center table featuring the Presidential Seal in multicolored faux marble stood in the entrance hall, a gift from the consul of Tunis. Life portraits painted in the White House by George Peter Alexander Healy hung in the parlor alongside those painted by Ralph Earl nearly two decades earlier when they were Congressman and Lady Polk. Images of political heroes Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson hung alongside political nemesis John Quincy Adams. A portrait of James Madison, the beloved husband of one of Sarah Polk’s closest confidantes, Dolley Madison, also warmed the imposing parlors.13

This French style chair was purchased in New York in 1848 by the Polks for their home.

Bruce White for The White House Historical Association/James K. Polk Ancestral Home CollectionSadly, James K. Polk’s meticulous planning came to naught. Even during his journey home, Polk ominously recorded in his diary the prevalence of cholera. He openly worried about his own health, and on June 1, 1849, he wrote, “During the prevalence of cholera I deem it prudent to remain as much as possible at my own house.”14 Two weeks later, Polk was dead from the terrible disease. He had lived in Polk Place just fifty-three days. His premature demise at age fifty-three makes him the youngest president to die, with the exception of those who have been assassinated. He had the shortest retirement of all the presidents.

Sarah Polk’s life was just half over at the time of her illustrious husband’s death. Living on in Polk Place she became the “Grande Dame” of Nashville society for the next forty-two years. Surrounding herself with the belongings that she and her husband acquired together, she lived her long life honoring James K. Polk in every way she could. Polk Place became her shrine, and she the curator. She closed off much of the house, occupying only a few rooms and some others needed for the use of the servants, her great-niece and adopted daughter. She gladly showed her home to most everyone who came to visit, including Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Grover Cleveland. She died in 1891 at the age of eighty-seven. Polk Place was torn down in 1901, in sadly depleted condition, never became the showplace that James and Sarah hoped for.

Today the Polk collection is on display at the James K. Polk Ancestral Home in Columbia, Tennessee, first opened to the public in 1929. Sarah’s great great niece helped the State of Tennessee purchase the only remaining home besides the White House that Polk had occupied and brought the collection there for public viewing.

President and Mrs. Polk purchased this Louis XV style chair for Polk Place in 1848. The purchase of the Philadelphia-made furniture was made through Alexander Stewart’s shop in New York City.

Bruce White for The White House Historical Association/James K. Polk Ancestral Home Collection

President and Mrs. Polk purchased this Louis XV style sofa for Polk Place in 1848. This fine furnishing was barely used by Polk before his untimely death from cholera just three months after leaving office.

Bruce White for The White House Historical Association/James K. Polk Ancestral Home Collection