Ushers and Stewards Since 1800

Copyright © Fall 2009 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

The door to the Usher’s Office is in the northwest corner of the White House Entrance Hall, a few steps away from the north door. The space has served this purpose since 1800.

Historic American Buildings SurveyThe White House Usher’s Office is one of the most singular working spaces in the world, with a tradition that parallels that of the presidents themselves. The actual quarters, adjacent to the Entrance Hall, serve as a platform from which to witness history. Remarkably few have had the distinct privilege of serving in this office, and the experience is like nothing else. Training can only be gained on the job, by directly meeting the daily demands of a presidential household, replete with official, ceremonial, and familial obligations. While presidents arrive at the White House with grand notions of shaping the country according to their political vision, first families come with hopes of inhabiting a comfortable, gracious, and hospitable home that meets their personal requirements and fulfills their need for peace and security. A century ago, author Gilson Willets wrote, “Compared to a human being, the White House, as a building, is the body; the home created within that body is the soul.”1 Creating that home is the responsibility of the domestic staff, led and coordinated by the Usher’s Office. The office sustains the core environment in which the president and his family will temporarily reside.

The designation “usher” is today a somewhat antiquated title dating to the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century, it was new to domestic establishments in the United States, though it was common in British stately homes. Once firmly established at the White House, it remained in continual use, principally for historical reasons. But the position’s myriad responsibilities have also proved difficult to harness within a more accurate title. According to Walker’s Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language (1831), an usher is “one whose business it is to introduce strangers, or walk before a person of high rank.” In Recollection of Men and Things at Washington (1869), L. A. Gobright aptly describes an usher as a “man-of-allwork.”2 When asked “What does an usher do?” former Chief Usher J. B. West replied simply, “I do what I’m told to do.”3 Certainly, it is the ability to adeptly juggle a broad range of responsibilities that has come to characterize White House ushers over the decades.

Principally, the Usher’s Office oversees the official and domestic life of the president, and the staff engages with first families at work and at play. It is by the ushers that presidents are witnessed as leaders, husbands, and fathers; they see the sorrow and joy, the exaltation and disappointment. Ushers are the first to welcome new presidents to the White House on inauguration day and the last to bid them farewell at the end of their tenure. Officially, the role of the Chief Usher is to serve as the “general manager of the Executive Mansion, and [he] is delegated full responsibility for directing the administrative, fiscal, and personnel functions involved in the management and operation of the Executive Mansion and grounds, including construction, maintenance, and remodeling.”4 Unofficially, it is the usher’s job to coordinate with the first family and to fulfill their wishes. The White House has been home to many great leaders, but it is the ushers, as seasoned custodians of White House customs, traditions and practices, that embody a lasting legacy of dedicated service.

A recent photograph of the Usher’s Office.

White House Historical AssociationWhile James Buchanan made the first use of the term “usher,” borrowing on his previous experience in Britain, it was not until the latter part of the nineteenth century that the title came into general use. Before that the primary domestic needs of White House inhabitants were served by stewards and doormen, and only scattered references have been found regarding the household employees of the early presidents. As precursors to ushers, stewards were responsible for greeting guests and those with appointments to see the president, appropriating necessary items from merchants, and directing routine housekeeping duties. As the usher’s job does today, these positions primarily required “patience, administrative ability, shrewdness as a purchasing agent, and a deep sense of discretion.”5 The individuals who served in these capacities were seasoned and devoted functionaries often bridging multiple administrations and taking on varied tasks according to the fluctuating needs of each first family. For example, President Rutherford B. Hayes’s steward, William T. Crump, stayed on under James A. Garfield, and Crump’s diverse duties led him to care for the ailing Garfield after he was shot. President Chester A. Arthur chose to employ a steward, although he served also as valet, a man he already knew, to cater to his taste for a fashionable, well-groomed wardrobe, and his doorkeepers were ordered to “wear a bit of ribbon in the lapel of their coats to distinguish them from guests.”6

Perhaps the earliest, specific reference to such a varied managerial position at the White House was in the Polk administration, when Henry Bowman was appointed to the post of “steward.” Mrs. Polk favored a business role for the steward, and she desired an individual to act jointly as a purchasing agent, household manager, and contractor for services, rather than solely as doorman or maître d’hôtel. Bowman resided in the White House, in the anteroom to the right of the north entrance that had previously functioned as the doorkeeper’s, and he utilized the space as both his bedchamber and his household office. This space was appropriately situated to witness the arrival and departure of guests and to supervise official functions and household activities. It remains an office space devoted to the ushers’ use to this day. The signature role of the new steward was to play an official part in presidential business by registering people who came to call upon the president, “ushering” them upstairs, and announcing them to the president.7 It is by assuming these duties that the new title of usher gradually began to be applied to the steward’s position.

Usher's Office in 1897 during the administration of President William McKinley

White House collectionAlthough the early administrations had servants with various types and titles, the only managerial position listed in the 1835 Federal Register is the principal gardener. Other household employees around this time were apparently paid by the president, served under him, and were not on the government payroll. In 1855, a doorkeeper at the President’s House, Edward McManus, is listed in the Federal Register for the first time, at an annual salary of $600. In 1857, Thomas Stackpole is listed as the doorkeeper, and an assistant doorkeeper was added at a salary of $438, but by 1861, Stackpole was listed as a watchman.8 Mr. Stackpole’s authority was obviously diversified again over the following years, because it has been noted that the “first duty of Mrs. Lincoln’s day was a consultation with the steward [Stackpole]” regarding the daily activities of the household.9 Similarly, in 1865, Stackpole made an inventory of the property of the White House and below his name is written the title of steward.10 Stackpole’s varied duties during his tenure at the presidential residence underscore the way in which the phrase “other duties as assigned” concisely characterizes the environment in which an usher attends the presidential household and further suggest the interchangeable nature of early domestic job titles.

In addition to employees like Stackpole, several others who served as doorkeepers or in other capacities during the Lincoln administration and later are not listed in the Federal Register. To provide a special guard for Abraham Lincoln, four police officers from the Metropolitan Police were detailed for duties at the White House in late 1864 and early 1865. These were Alphonso Donn, John F. Parker, William H. Crook, and Thomas Pendel. Of these, Crook and Pendel remained at the White House for many years and are usually referred to as doorkeepers. However, in his memoirs, Colonel William H. Crook relates his appointment as “Executive Clerk to the President of the United States” on December 20, 1870, and his subsequent designation as “Disbursing Agent for the disbursement of the salary and contingent funds of the Executive Mansion” on March 3, 1877, by President Ulysses Grant.11 It seems that trusted employees served wherever they could be most useful to presidential families—as doorkeepers, watchmen, stewards, and ushers.

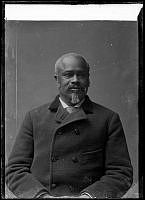

William Slade was the first bonded steward or usher, under President Andrew Johnson. This portrait, an attribution, is believed to be his only likeness.

Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and MuseumWilliam Slade, who was African American, was the first bonded steward or usher, under Andrew Johnson. He was likely the “William” who had served Lincoln as valet in 1864–65. After Slade, White House stewards, usually also referred to as ushers, were federal, bonded employees under the Department of Interior, appointed by the president. They managed much of the growing domestic staff, including the maids, footmen, cooks, and laborers, as well as the public funds appropriated by Congress for the Executive Mansion. The position was also responsible for keeping the keys to the locked pantry in which the White House valuables, such as the silver, gold plate, and china services, were stored, and it has been noted that President Arthur’s steward was under a bond of $10,000 as a result of his added accountability.12

Perhaps in official recognition that the administration of the presidential household was becoming increasingly complex, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Edson S. Dinsmore to the post of chief doorkeeper (also called chief usher) in 1889 at a salary of $1,800. By establishing a clear hierarchy within the ranks of the White House domestic staff, Harrison demonstrated the need for more focused management of presidential activities and the growing domestic workforce. Closely following his predecessor’s actions, President Cleveland placed William Dubois on the White House personnel payroll as chief usher in 1893, thereby firmly placing the Usher’s Office in a preeminent position over household affairs.

Colonel William Crook was detailed from the Metropolitan police to protect Abraham Lincoln in 1864 and remained at the White House through many presidencies. He is seen here with other members of President McKinley’s staff, c. 1900. From left to right Col. Crook, Warren Young, Benjamin F. Barnes, George Bruce Cortelyou, Rudolph Forster, Octavius L. Pruden, and Major Benjamin F. Montgomery.

Library of CongressAs the nineteenth century drew to a close, and communication and travel between Washington and foreign nations became easier, the White House began to receive international visitors. These brought to the halls of the Executive Mansion “standards of social life and an atmosphere of formality,” said Colonel Crook, “not previously practiced.”13 It fell to the Usher’s Office to establish specific protocols and consistently maintain a punctilious attitude about all household matters, small and large, seen and unseen. The authority to whom they turned for advice was Alvey A. Adee, third secretary (and sometimes second secretary) of State, rather a oneman protocol office. Clearly, it had been well demonstrated that a desirable, if not crucial, personality trait for any of these positions, but increasingly so for the usher, was adaptability. Howell G. Crim, chief usher between 1938 and 1956, charged that “Nothing is a problem . . . it’s all in a day’s work—and there is no such thing as an average day.”14 Over the years, it has become common practice for an usher to expect the unexpected, and an usher’s success hinges on the ability to “remain calm and unflappable at all times—even when searching the White House for Caroline Kennedy’s lost hamsters or hastily devising a cage for two wild tiger cubs Mrs. Kennedy sent word she was bringing back from India,” as West did during his tenure as usher.15

The advent of the Theodore Roosevelt administration brought further reorganization to the White House staff. Although First Lady Edith Roosevelt chose to retain final responsibility for the presidential residence, the president and his wife created a framework that formally ceded all remaining responsibilities held by the steward and doorkeeper to the chief usher. The last steward to hold the official position was Henry Pinckney, President Roosevelt’s personal valet, an African American prominent in Washington. Thomas Stone was appointed chief usher in 1903. In the reorganized White House, the Roosevelts’ usher staff included nine ushers, each answering to the chief usher. Six ushers were on duty at all times, and they managed the daily running of the White House, ordered needed supplies, hired and trained and, when necessary, released domestic staff, made arrangements for social events held at the White House, and ensured the comfort and security of each White House guest.16

With the arrival of President William Howard Taft and First Lady Helen Taft at the White House in March 1909, further innovations were instituted in the duties of the domestic personnel. A female housekeeper, Mrs. Elizabeth Jaffray, a Canadian, was employed to execute duties previously performed by the stewards. According to Mrs. Jaffray’s memoir, Mrs. Taft interviewed her for the position and plainly stated, “Mr. Taft and I are contemplating changing the plan of running the White House. There has always been a steward for the routine management, and outside caterers have been brought in for the State functions and great dinners. We are thinking of getting a housekeeper and manager and doing away with both the stewards and caterer.”17

Ike Hoover, White House usher 1889–1913, chief usher 1913–33, by Philip de Laszlo, 1932.

Collection of Set MomjianAlthough the allotment from government funds for the housekeeping position was only $1,000 per year, Mrs. Jaffray accepted it and remained housekeeper for seventeen years. The ushers, relieved of their doorkeeper duties, were retained to perform tasks determined more in keeping with a management position. Although the Roosevelts had an extensive staff of nine ushers, the Tafts retained only two, Tommy Pendel and Irwin Hoover; the remaining seven were transferred to positions within the Executive Office. Irwin “Ike” Hoover, who had gone to the White House on May 6, 1891, to install the first electric lights and remained as White House electrician, was promoted to the usher’s force in 1904 by President Roosevelt. Under the Taft administration, he was elevated to chief usher, a post he held until his death in 1933.

With the appointment of Hoover as chief usher, the job began to take the shape familiar to us today. Meeting challenges similar to those of the modern ushers, Ike Hoover must have found his daily activities charged with both definition and contrast. While he navigated the daily rituals as executive head of the household, he was also in charge of the arrangements for the wedding of President Woodrow Wilson and Edith Bolling Galt, including obtaining the marriage license. Later he stood by Wilson’s side in the Usher’s Office as the president signed the war resolution that brought the country into World War I. Ike Hoover encapsulated the role of chief usher in the following explanation:

The Chief Usher passes judgment on the eligibility of every person who crosses the threshold. In consultation with the First Lady and the President, he makes all plans for any form of entertainment or hospitality, personal, social or official, and is present to see that the plans are carried out. He is responsible under the President and his wife for every guest, he is the keeper of precedents and he carries a figurative oil can with which to lubricate all frictions. He is on the job as much as sixteen to eighteen hours a day; Sundays and holidays are only words to him.18

Of Hoover it was once said, [he] “is the pivot around whom the Presidential ‘state’ revolves. There would seem to be no ‘spare part’ for him and no incitement toward any thought of one. Legitimate exaggeration would say about him that his tact makes him invisible and his experience makes him indispensable.”19 Hoover was destined to become the first in a short line of men who have expertly and efficiently served the presidency in this unique capacity.

Howell Crim, chief usher from 1938 to 1956, is pictured at work in his temporary office at Blair House during the Truman renovation.

Collection of Howell B. Crim, Jr.

J.B. West, chief usher from 1957 to 1968, poses in the West Sitting Hall with Jacqueline Kennedy and John Kennedy Jr. prior to their departure from the White House following the assassination of President Kennedy. Mrs. Kennedy signed the photograph for West at Christmas 1963.

John F. Kennedy Presidential LibraryDue to their direct responsibility for the personal comfort of the presidential household and their guests, the members of the Usher’s Office are often viewed as an “office family” by the presidents they serve and, as such, often develop special relationships with White House residents. Gary Walters, chief usher from 1986 to 2007, has said, “It is our responsibility, as servants of the presidency, to make sure that the president and first lady get the very best of care that we can provide.”20 It is through this acute sense of responsibility and the intimate nature of their daily interactions that close bonds between the ushers, especially the chief ushers, and first families have been forged. Immediately following West’s death in 1983, Mrs. Kennedy asked First Lady Nancy Reagan to secure permission for him to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery as a tribute to his exceptional service to six presidents. Mrs. Kennedy once called West “the most powerful man in Washington next to the president,” and said, “I think he is one of the most extraordinary people I’ve ever known.”21 In honor of his dedicated service, President Reagan graciously made an exception to Arlington’s rules, which permit burial only of career military personnel or recipients of military awards, unless the president decides otherwise. A more light-hearted tribute was bestowed by Mrs. Reagan when she chose to name her Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Rex, as a reminder of the loyal and faithful service of Rex W. Scouten, chief usher to four presidents. Scouten returned from retirement to become curator of the White House for the Reagans.

The chief usher of the White House is responsible for overseeing all of the preparations for a State Dinner. Chief Usher Rex Scouten is seen with Maitre d'hotel John W. Ficklin discussing the set up for a dinner in the State Dining Room in 1970, early in the Richard M. Nixon administration.

White House Historical AssociationCurrently, the Usher’s Office operates with a staff of seven, including a chief usher, deputy chief usher, four assistant ushers, and one executive assistant. Working two shifts a day, the ushers administer a residence of 132 rooms, manage official and ceremonial events ranging from formal state dinners to holiday receptions, and oversee a vast collection of fine and decorative arts. In essence, the Usher’s Office manages one building utilized in three unique ways—a private home, a venue for events, and an historic house museum. But first and foremost, the White House is a home. All decisions must be balanced against the maintenance of privacy and the preferences of the first family.

To more effectively illustrate the job responsibilities of chief usher and modernize the job title, the designation was augmented in 2007 to “director of the Executive Residence and chief usher.” Appointed by President George W. Bush, the first person to hold this new title is Stephen W. Rochon, a retired rear admiral in the U.S. Coast Guard with a background in personnel management, strategic planning, and effective interagency coordination.

Gary Walters in the Blue Room supervises the preparation of plates to be carried into a dinner during the William J. Clinton administration in 1994.

Collection of Gary WaltersAlthough the traditional title has been modified slightly, there remains an undercurrent of pride in the Usher’s Office. Its long-standing tradition of service makes it able to transcend political parties and personalities. Ike Hoover closed his memoir with these thoughts about his staff, “They seem to feel and appreciate the importance and responsibility of their positions. Especially among the older employees, those who have been through several administrations, there is a loyalty born of time and experience. Administrations change from one political faith to another, but these old fellows go on serving faithfully.”22 More than forty years after Hoover penned those thoughts, West wrote, “My loyalty was not to any one President, but rather, to the Presidency, and to the institution that is the White House.”23 Similarly, Walters acknowledges that the legacy of the Usher’s Office is based on deep respect for the privacy of the first families, which, in turn, fosters credibility between them and the domestic staff. In a 2007 C-SPAN interview at the time of his retirement Walters emphasized that the White House is “first of all a home.”24

Elizabeth Jaffray, housekeeper at the White House from 1913 to 1925 once observed that the presidential residence “is no remote castle, but a plain white house—a home full of the hundred and one petty details, triumphs, worries, heartaches, and pleasures that every home faces.”25 It is these so-called petty details that the ushers manage for White House residents. No detail is considered insignificant when it relates to the material comfort, privacy, or well being of the first family. However, to every extent possible, it is also the responsibility of the ushers to make the mechanics of their work invisible, creating a seamless and smoothoperating household. Ushers, wrote Willets in 1908, have had the privilege of overseeing the “humor and wit of the State dinner, the romance and marriage and honeymoon of Presidents, their brides, their sons, their daughters, . . . fun and frolic on festive occasions, . . . historical ceremonies, . . . and occasions of gaiety, then of gloom.”26 In essence, the same holds true today.

The three recent chief ushers posed in the White House Entrance Hall at the foot of the Grand Staircase in 2008. Left to right: Rex Scouten held the position of chief usher from 1969 to 1986; Gary Walters from 1986 to 2007; and Rear Admiral Stephen W. Rochon, USCG (ret.) from 2007 to 2011.

White House Historical AssociationStewards and Ushers of the White House: 1800-Present

John Briesler

Steward to John Adams, 1800–01

Joseph Rapin

Steward to Thomas Jefferson, 1801

Etienne Lemaire

Steward to Thomas Jefferson, 1801–09

Jean-Pierre Sioussat

Steward to James Madison, 1809–17

Joseph Jeater

Steward to James Monroe, 1817–25

Antoine Michel Guista

Steward to John Quincy Adams, 1825–29

Steward to Andrew Jackson, 1829–33

Joseph Boulanger

Steward to Andrew Jackson, 1833–37

Steward to Martin Van Buren, 1837–41

Steward to William Henry Harrison, 1841

Steward to John Tyler, 1841–45

Henry Bowman

Steward to James K. Polk, 1845–49 Ignatius Ruppert

Steward to Zachary Taylor, 1849–50

Steward to Millard Fillmore, 1850–53

William H. Snow

Steward to Franklin Pierce, 1853–57

Louis Burgdorf

Usher to James Buchanan, 1857–59

Richard Goodchild

Usher to James Buchanan, 1859–61

Usher to Abraham Lincoln, 1861

Jane Watt

“Stewardess” to Abraham Lincoln, 1861–62

Pierre Vermereu

Steward to Abraham Lincoln, 1862 (?)

Mary Ann Cuthbert

Stewardess to Abraham Lincoln, 1862–63

Thomas Stackpole

Steward to Abraham Lincoln, 1863–65

Steward to Andrew Johnson, April–June 1865

William Slade

Steward to Andrew Johnson, 1865–69

Valentino Melah

Steward to Ulysses S. Grant, 1869–77

William T. Crump

Steward to Rutherford B. Hayes, 1877–81

Steward to James A. Garfield, 1881

Steward to Chester A. Arthur, 1881–82

Howard Williams

Steward to Chester A. Arthur, 1882–85

William Sinclair

Steward to Grover Cleveland, 1885–89

Steward to Grover Cleveland, 1893

Steward to William McKinley, 1897–1901

Hugo Zieman

Steward to Benjamin Harrison, 1889–91

William McKim

Steward to Benjamin Harrison, 1891–93

Edson S. Dinsmore

Chief Usher to Benjamin Harrison, 1889–92

William Dubois

Steward to Grover Cleveland, 1893–97

Henry Pinckney

Steward to Theodore Roosevelt, 1901–9

[five assistant ushers appointed]

Thomas E. Stone

Chief Usher to Theodore Roosevelt, 1903–9

[five ushers raised to nine in number, assisting chief usher]

Chief Usher to William Howard Taft, 1909–11

[Archibald Butt, a military aide, actually held the authority from 1908 to 1912; when he died on the Titanic position of “steward” dies out]

Irwin “Ike” Hoover

Chief Usher to William Howard Taft, 1913

Chief Usher to Woodrow Wilson, 1913–21

Chief Usher to Warren G. Harding, 1921–23

Chief Usher to Calvin Coolidge, 1923–29

Chief Usher to Herbert Hoover, 1929–33

Chief Usher to Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933 until his death September 14, 1933

Raymond Douglas Muir

Chief Usher to Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1933–38

Howell G. Crim

Chief Usher to Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1938–45

Chief Usher to Harry S. Truman, 1945–53

Chief Usher to Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1953–57

J. B. West

Chief Usher to Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1957–61

Chief Usher to John F. Kennedy, 1961–63

Chief Usher to Lyndon B. Johnson, 1963–69

Chief Usher to Richard M. Nixon, 1969

Rex W. Scouten

Chief Usher to Richard M. Nixon, 1969–1974

Chief Usher to Gerald R. Ford, 1974–77

Chief Usher to Jimmy Carter, 1977–81

Chief Usher to Ronald Reagan, 1981–86

Gary Walters

Chief Usher to Ronald Reagan, 1986–89

Chief Usher to George H. W. Bush, 1989–93

Chief Usher to Bill Clinton, 1993–2001

Chief Usher to George W. Bush, 2001–7

Stephen W. Rochon

Chief Usher to George W. Bush, 2007–9

Chief Usher to Barack Obama, 2009–2011

Angella Reid

Chief Usher to Barack Obama, 2011 - 2017

Timothy Harleth

Chief Usher to Donald Trump, 2017 - 2021