The phrase "The Half Had Not Been Told Me" is taken from a Biblical reference Frederick Douglass used to describe the beauty of the new Freedman's Savings Bank and Trust building, once located on Lafayette Square. Douglass compared the experience of seeing the building for the first time to the way the Queen of Sheba, an African queen, felt upon seeing the riches of King Solomon. Douglass wrote, "The whole thing was beautiful. . . I felt like the Queen of Sheba when she saw the riches of Solomon, that 'half had not been told me'."

Lafayette Square—known first as President's Square—is a landscape with a rich and varied African American history. Prior to emancipation, both free and enslaved African Americans lived and worked here. The area has also been home to important institutions, such as the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank and the Belasco Theater, one of the few venues in segregated Washington where black entertainers were allowed to perform before desegregated audiences. And it has been a place where people took a stand—from an enslaved woman who sued Henry Clay for her freedom in 1829 to citizens gathering at St. John's Church in 1963, in preparation for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Just like the riches of King Solomon that Frederick Douglass referred to, the African American history of Lafayette Square is indeed a treasure.

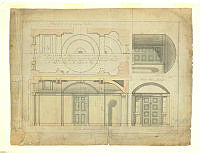

Decatur House

For most of its history, Decatur House served as home to numerous enslaved and free African Americans who lived and worked at the site – and its architecture, in several ways, reflects the status of those African American residents. The two remaining original structures – the 1818 residence facing Lafayette Square and the ca. 1822 slave quarters – generally evidence the living and working conditions of enslaved men and women in urban areas as well as their owners’ desires to hide their activities from plain view.

Architect B. Henry Latrobe designed Decatur House with various access passages for a variety of different people, with the movements of enslaved people in particular tightly controlled to allow for high work efficiency but low visibility. A back stairway and an exit directly out of the kitchen onto H Street provided ways for relatively invisible movement throughout the house. Ironically, whereas the neoclassical style of Decatur House represented the egalitarian ideals of the early republic, the service spaces represented the most glaring contradiction of American democracy – the institution of slavery.

The Slave Quarters at Decatur House

The slave quarters at Decatur House is one of only a few remaining examples of slave quarters in an urban setting, and also is uniquely significant as the only remaining physical evidence that African Americans were held in bondage within sight of the White House. Though the exact date of construction is unknown, records indicate the quarters possibly were built as a one story structure as early as September 1821 during the tenancy of the French foreign minister, as a bill for $40.40 notes iron work and a “door & frame for oven” for “back buildings,” perhaps suggesting a cooking facility of some sort. Further, a January 1822 bill for more than $1300 also indicates the cost of “erecting a building joining the “house in Presidents Square.”

John Gadbsy, the second owner of Decatur House, likely expanded the structure both up and out in 1836 to provide more working and living space for the large number of enslaved people – perhaps who supported his nearby National Hotel. Evidence also indicates that the first floor of the quarters served as a kitchen, laundry, and dining area for the enslaved members of the household, while the second floor served as their living quarters.

Reflecting the historical perspective of the time regarding what was considered “significant” in American history, the National Trust for Historic Preservation removed a great deal of the interior architectural fabric of the slave quarters in the 1960s to install a shop on the first floor and Trust offices on the second. However, today, the second floor in of the quarters in particular is undergoing intense investigation, and floors, windows, and chimney breasts are all being revealed and interpreted for their original intent. Read More

Decatur House & Charlotte Dupuy

Few people know the story of a brave woman named Charlotte Dupuy who was enslaved by Secretary of State Henry Clay at Decatur House, the large brick residence that has stood on Lafayette Square at the corner of H Street and Jackson Place since 1818. Read More

St. John's Church

Every president since James Madison has attended services at St. John's Church. This distinctive yellow church was the second building to be constructed on Lafayette Square and has always been a symbolic and important house of worship in Washington, D.C. Visitors to Lafayette Square can enter St. John's Church from the 16th Street entrance to see the sanctuary and the Presidents' Pews. Read More

Dolley Madison's House

Did you know that after her husband's death, First Lady Dolley Madison was so poor that she had to accept money from a former slave and hand-outs from her neighbors on Lafayette Square? The yellow house on the corner of H Street and Madison Place was Dolley Madison's home from 1837 until her death in 1849. Read More

Tayloe House

Five hundred and forty-seven dollars and fifty cents. According to the records of the District of Columbia that is the amount that Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, who lived on Lafayette Square, was paid by the federal government for Melinda Lawson, a slave he was forced to free under the District of Columbia Emancipation Act passed by Congress and signed by Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. Read More

Rodgers House/Belasco Theater

The Rodgers House, formerly at 717 Madison Place, was constructed in 1831 by Commodore John Rodgers, a high-ranking naval officer. The Belasco Theater, originally known as the Lafayette Square Opera House when it opened on September 30, 1895, was an impressive six-story building with an auditorium that seated one thousand people. Read More

Freedman's Savings & Trust Co.

Three million dollars belonging to 61,000 African Americans. That's how much accumulated wealth vanished when the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company failed in June 1874. Earlier that year, Frederick Douglass had become the bank's President just after it moved its headquarters to a prominent location on the southeast corner of Lafayette Square, where the Treasury Annex now stands. Read More

Lafayette Square

In 1810 an enslaved woman named Alethia “Lethe” Tanner purchased her freedom with $275 she had earned from selling vegetables in the area that we know today as Lafayette Square. Enslaved people used the open air markets to their advantage, by growing fruits and vegetables on small plots of land and selling them to raise money. Read More

The White House

To imagine what it was like here when the White House was being constructed in the 1790s, erase everything else you see now on and around Lafayette Square. The park was a field—muddy or dusty, depending on the weather. Enslaved workers who were building the White House were housed in temporary shelters—each about 10 feet wide and 10 feet long—lined up in rows on the east and west sides of the field. Read More

712 Jackson Place

Many people know the sensational story of Congressman Daniel Sickles who shot his wife's lover in broad daylight in 1859 on Madison Place, the street on the east side of Lafayette Square. What fewer people know is that another killing—one that captivated the city because of its racial undertones—happened in 1918 on the opposite side of the Square, in the building that is today 712 Jackson Place and the home of the Truman Scholarship Foundation. Read More

Ewell House

On April 30, 1819 Thomas Ewell, a former naval surgeon and prominent physician who built a house about where 734 and 736 Jackson Place are located today, placed an ad in the National Messenger looking for an enslaved woman named Daphne who had run away. Read More

Daniel Webster's House

Before the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Building was built during 1922-25, a simple three-and-a-half story brick home stood in its place at the corner of H Street and Connecticut Avenue. The home's original owner was Daniel Webster, a Congressman from both New Hampshire and Massachusetts and a Senator from Massachusetts who also served as Secretary of State for three Presidents. Read More

Elizabeth Keckly

Born into slavery in 1818, Elizabeth Hobbs Keckly (also spelled Keckley) learned to sew from her mother and this skill would eventually bring her freedom and success. She developed into an accomplished seamstress and the income from her dressmaking supported the family that enslaved her. Read More

Wormley Hotel

From the humble beginnings of an African American family which had lived and worked in the White House neighborhood since the earliest years of the century, the hotel's founder, James Wormley, developed an internationally renowned hospitality business catering to the most prominent visitors and residents of the capital. Read More