Ewell House

Buying, selling, and resisting.

Copyright © White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

Newspaper advertisements placed by Thomas Ewell offering a reward for the return of runaway slave Daphne.

Though the people who enslaved African Americans on Lafayette Square were rich, powerful, and prominent, their slaves fought back against being held in bondage. One way they did so was by running away. On April 30, 1819 Thomas Ewell, a former naval surgeon and prominent physician who built a house about where 734 and 736 Jackson Place are located today, placed an ad in the National Messenger looking for an enslaved woman named Daphne who had run away. The ad described Daphne as, "black, of middle height, rather corpulent – wife to a noted negro brickmaker called Bill Slaughter." Ewell's ad also stated that "for several days she has been sculking about Georgetown. . . I will pay five dollars and all necessary expenses incurred for her apprehension and delivery to me near the Presidents House." However, we know Daphne evaded capture since another runaway ad was put out for her in 1824. The ad states she was "concealed in Georgetown" and presumably left the area. This indicates that Daphne probably made use of the extensive networks between free and enslaved African Americans to aid in her escape. Free and enslaved African Americans built a strong foundation and pooled money and resources to help people buy their or their family's freedom or escape when necessary. These resources were also essential to building schools, churches and businesses. Her story is an important example of the power of these connections within Washington's African American community, as well as of self-emancipation.

Daphne was not the only person Ewell enslaved. In the 1820 census the Ewells' Lafayette Square household contained five enslaved African Americans, 2 males and 3 females all under the age of 14, and 11 white people.

Thomas Ewell not only owned slaves, but he also bought and sold enslaved people. Though he viewed his slaves as property, Ewell did demonstrate some concern for what happened to the people he sold. On January 31, 1820, he placed this classified advertisement in the Daily National Intelligencer. It read, "The subscriber has for sale a negro woman, without any children, aged about 30 years; an excellent cook and washer. Also one of the most handy male servants in the country, used to waiting and driving carriage. Also, he will have, in a few days a woman with fine likely children of very promising qualities. Those servants will be sold for half the sum that was refused for them last year; and are only being sold to pay debts which cannot be postponed. A preference will be given to purchasers who will carry them westward, where the plenty of produce lessens the pains of slavery." Nonetheless, in spite of his consideration, "produce" would not lessen the pain of being ripped away from family, friends, and social networks they developed in the area. The domestic slave trade in Washington, D.C. and elsewhere was a destructive force which highlighted the enslaved people were considered commodities by slave holders to be bought and sold whatever their reasoning.

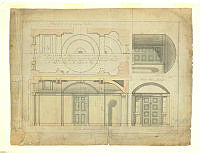

The Ewell House was demolished and replaced by these buildings that were designed to look historic.