Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Slavery and Strategy in Decatur House

Charlotte Dupee’s Suit for Freedom in Early Washington, D.C.

This article is part of the Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood initiative. Explore the Timeline

Silhouette of Charlotte

The White House Historical AssociationOn February 11, 1829, members of Congress convened to certify votes for President and Vice President of the United States as Andrew Jackson had recently defeated incumbent President John Quincy Adams after an acrimonious campaign.1

As the Adams administration came to an end, Secretary of State Henry Clay made plans to vacate his post in Washington and return to Ashland, his Kentucky plantation. But before Clay could leave the capital, he received a shocking notice. Claiming that she was born of a free woman and wrongfully enslaved, Charlotte Dupee, a woman enslaved by Henry Clay for nearly twenty-three years as of 1829, was suing the powerful statesmen for her freedom and the freedom of her son Charles and daughter Mary Ann.2

Dupee's Freedom Suit

Timing was the linchpin of Charlotte Dupee’s freedom suit. Having lived and worked in Decatur House, a townhouse on Lafayette Square, since 1827 – with regular proximity to Henry Clay, his esteemed guests, and their conversations – Dupee likely overheard political news, including discussions about slavery. This exposure to such discourse helps us understand why Charlotte Dupee purposefully filed her petition against Clay in between the time the presidential election results were certified and Clay’s return to Kentucky. Doing so enabled Dupee and her lawyer, Robert Beale, to take advantage of favorable freedom suit legal precedents in the District. Moreover, D.C. law required petitioners to remain in the District during litigation. While Henry Clay returned to Ashland, Dupee awaited the outcome of her freedom suit without her family at Decatur House. That physical distance between enslaver and enslaved was crucial: Dupee now exercised a unique degree of freedom in the nation’s capital.

In May 1830, the court ruled against Charlotte Dupee. Her formal petition for freedom was denied. Though she continued to resist Clay’s demand that she return to Kentucky, Dupee eventually reconnected with her family at Ashland where she and her daughter, Mary Ann, were manumitted in 1840. Aaron Dupee – Charlotte’s husband whom Clay enslaved for over twenty years – remained enslaved at Ashland through the Civil War. While documentation is scant, Charlotte likely lived with Aaron around Lexington in Fayette County, Kentucky, for the remainder of her life. It is also worth noting that there are multiple spellings of their surname, including Dupuy and Dupuis; and while Charlotte’s preference is unknown, this article will use “Dupee” as this is the post-manumission spelling of her last name.3

Decatur House had stood at the corner of 16th and “H” streets for nearly a decade when Charlotte Dupee entered the brick townhouse in 1827, enslaved to Henry Clay. At approximately forty years old, Dupee became one of the first recorded enslaved people to live and work in Decatur House. Publicly, Decatur House had become the preferred dwelling for foreign ministers and secretaries of state, and frequently hosted gatherings of Washington’s social elite. But those four decades of Charlotte’s life before Decatur House were influential when she decided to sue for her freedom in 1829. Therefore, we should briefly acknowledge the experiences that Dupee brought with her when she arrived at Decatur House.

George Standley, Charlotte’s father, lived as a freeman in Dorchester County, Maryland, since 1790. During that time, he likely worked, budgeted, and saved enough money to purchase the freedom of his family members still held in bondage – a common freedom strategy on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.4 Eventually, George Standley bargained with his former enslaver and the current enslaver of his wife and children, Daniel Parker, to purchase the freedom of his family. Charlotte’s father George succeeded, but only partially. Standley did purchase the freedom of Charlotte’s mother, her sister, and her brother. But Charlotte herself was not included in the transaction.5 The historical record does not clarify why George did not purchase Charlotte in the 1792 transaction. One imagines that Dupee’s gender, young age, and reproductive potential may have factored heavily into the bargaining.6

Dorchester County, Maryland, is located between the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay and the western border of Delaware. Cambridge, Maryland, where James Condon enslaved Charlotte Dupee before displacing her to Kentucky, is 56 miles east of Washington, D.C.

Library of CongressCharlotte remained enslaved for another five years before Parker sold her to a local man named James Condon around 1796. Under Condon’s enslavement, Dupee likely carried out domestic duties, reared the Condon children, and worked with Condon’s apprentices. These apprentices later provided testimony in Charlotte’s freedom suit that illuminated Dupee’s enslaved life under Condon.7

In the spring of 1805, James Condon ripped Dupee from her home, her family, and her kin network in Maryland and forcibly transported her hundreds of miles west to Lexington, Kentucky. Upon settling in Kentucky, Condon made financial decisions that signaled a desire to move up the genteel social ladder. Within a year, two important developments occurred. First, James Condon relocated his tailoring business to a more prominent, perhaps more expensive location on Lexington’s Main Street. Second, Charlotte seems to have begun seeing another enslaved person named Aaron Dupee. Aaron worked as a manservant to an up-and-coming politician named Henry Clay. Some historians argue that as Charlotte and Aaron’s relationship evolved, Aaron advocated for Henry Clay to purchase Charlotte so that Aaron and Charlotte could live together. Such a transaction occurred in March 1806 when Condon sold Charlotte Dupee for “a very high price” to Henry Clay. Charlotte was once again relocated, this time to Clay’s Ashland plantation near Lexington.8

Henry Clay had enslaved Charlotte Dupee for over twenty years when Charlotte arrived at Decatur House in the spring of 1827. Here, in the President’s Neighborhood, Dupee became more interconnected with Washington’s three main demographics – white, free Black, and enslaved – than at any other time in her life. She also arrived in a city heated with political debate. Much of this discourse revolved around the topic of slavery – and Henry Clay was often at the heart of the debates.9

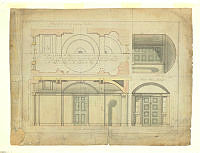

Decatur House

White House Historical AssociationCharlotte likely lived in the servants’ wing of the house alongside her family. The Decatur House Slave Quarters evolved over time from a service wing in 1821 to an urban slave quarters when Charlotte moved in during the spring of 1827, though it is possible that enslaved people lived in the space previously. Dupee’s presence in these places, the conversations heard and had, and events observed and engaged with likely shaped her quest for freedom.10

Though she likely served as a domestic servant to the Clays, that also meant that Charlotte Dupee would have (limited) access to powerful white socialites and politicians as she waited on them at the Clays’ parties. While Charlotte Dupee was not free during this time, she likely engaged with free domestic servants at markets or on the street, communicated with enslaved workers in her quarters or at work sites, and overheard conversations of influential white people dining at Decatur House. She also likely overheard news of other freedom suits in the District – many of which were successful. Ideas and models of freedom abounded for Charlotte.11

Inside of Decatur House Slave Quarters, William Kelly, March 2019

William KellyAs politicians debated the course of American slavery in the 1820s and 1830s, Charlotte’s enslaver was often at the center of the discourse. Throughout his political career, Henry Clay’s stance on slavery vacillated between viewing the system as a “necessary evil,” favoring gradual abolition of the enslaved, and even advocating for the forced colonization of Black people to West Africa (Clay was one of the founders of the American Colonization Society at the organization’s inaugural 1816 meeting in Washington, D.C.) While Clay may have had varying public stances on slavery, the famous statesman’s actions were more definitive.12

Portrait of Henry Clay, 9th Secretary of State Under President John Quincy Adams.

The Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C.In March 1828, less than one year before Charlotte sued for her freedom, a memorial advocating for the gradual abolition of slavery in the District was presented to Congress. Henry Clay did not join the nearly 1,000 signatories who declared slavery not a “necessary evil,” but “an evil of serious magnitude.” However, many of his influential Washington peers did sign: at least three judges of the D.C. Circuit Court (most notably Chief Judge William Cranch) and Charlotte Dupee’s future lawyer, Robert ‘Beal’ (Beale).13

To Charlotte the paradox was likely evident: while politicians attempted to scrub away the stain of slavery from Washington’s palaces of liberty, the insidious institution persisted. With the memorial relayed to Congress and the debate over slavery in the District raging, Charlotte Dupee remained at Decatur House – in close proximity to the political tumult.

Equipped with a lifetime of interactions with freedom – from Maryland to Kentucky to Washington, D.C. – Charlotte Dupee filed her suit on February 13, 1829. With a lawyer, Robert Beale, experienced in representing petitioners for freedom, Charlotte based her case upon two main premises: that she was born to a free mother, and that her former enslaver, James Condon, promised Dupee her freedom on a conditional basis, which she claimed to have met.14

Dupee Petition

John Quincy Adams’ failed bid for the presidency catalyzed Dupee’s campaign. With Clay customarily resigning his position as secretary of state and preparing to return to Kentucky, Dupee had to act quickly. If she decided to act while Clay was still in Washington, he might stymie her efforts. If Dupee waited too long, she could be taken back to Kentucky, restricted by more stringent slave codes, and lose her opportunity to sue for her freedom all together. But, as the petitioner, D.C. law mandated that Charlotte stay within the boundaries of the District while the case was tried.15

While it is a possibility that Henry Clay’s political adversaries could have attempted to persuade Charlotte into suing Clay, it is more likely that Charlotte and her lawyer strategized and sued on their own accord. By choosing to sue for her freedom mere weeks before he left the city, Charlotte was able to stay in the District and maintain a unique degree of independence from her enslaver. While Clay returned home to Kentucky to await the trial’s outcome with Charlotte’s husband and two children, Dupee stayed at Decatur House where the new Secretary of State, Martin Van Buren, paid her wages.16

Archival evidence does not describe the detailed minutes of Charlotte Dupee’s trial, but remarkable letters that Clay wrote around the trial reveal the broader impact of Dupee’s suit. Though Clay claimed he knew nothing of Dupee’s intention to file for her freedom, the mere optic of the suit provoked a strong rejoinder. After he received a summons from the Circuit Court, Clay immediately penned a response defending his honor and character. Justifying the legality of his 1806 purchase and ownership of Dupee, Clay explicitly denied “that the petitioners...have any right, or just claim whatever, to their freedom.” Clay proceeded to lay out his argument in chronological order in a tone typical of the self-perceived role as a benevolent slave owner. After all, Clay contended, he was the one who allowed Dupee to visit her family on the Eastern Shore in 1816 and again during the summer of 1828. To Clay, the only impetus behind this suit was a cynical one; it had to be the work of his political enemies.17

Clay was not alone in this theory. There is no known documentation of agreed conditional manumission between Charlotte and her second enslaver, James Condon, which threatened the legal argument of Dupee’s case. But Henry Clay inquired of James Condon if this really was the case. Condon replied in a manner similar to Clay’s: a gentleman concerned for his own character, honor, and standing. Indeed, Dupee’s pursuit of freedom also meant evaluating the reputations of two prominent slaveholding politicians.18

Condon defended his enslavement and eventual sale of Charlotte to Clay by depicting himself as a vulnerable, elderly man who would never think of illegally practicing slavery, especially in a transaction with a man of Henry Clay’s stature. He vouched for his integrity and blamed Dupee for any perceived wrongdoing.19

However, in his letter Condon makes a surprising admission. After spending the majority of the correspondence defending himself and his character, Condon divulged to Clay one “reflection [that] has occur[re]d to my mind & perhaps it may have had some influence upon her [Charlotte Dupee’s] mind.” He admitted that he might have promised Dupee her freedom long ago. But this was “predicated upon the Condition of long & faithful services” by her unto Condon. When testimony was collected, interrogations of Condon’s apprentices in Maryland addressed this same question, but their fingers pointed toward Mrs. Condon. John Mowbray, who moved into the Condon’s household after Charlotte, testified that “while in Condon's family I...frequently heard Mrs: Condon say, at times when a little provoked with Lotty's conduct, that she (Lotty) should not be free so soon as Lotty expected. I have also heard in Condons family that Lotty was promised her freedom; whether by James Condon, his wife, or Daniel Parker I do not know." Whether it was James Condon or his wife, a verbal promise of freedom seems to have been made to Charlotte Dupee sometime between the mid-1790s and 1806.20

Ashland. The Homestead of Henry Clay.

Princeton Graphic Arts CollectionAdmissions like these worried Clay. Quick to recover, Condon shifted the blame from himself and his wife to Charlotte Dupee. No matter what promise was allegedly made, he argued, it was void by the time she filed for her freedom. According to Condon’s reasoning, Charlotte violated any promise when she married Clay’s Ashland manservant, Aaron Dupee, which some historians believe led to her sale to the then-senator. In Condon’s view, she had not kept her promise of “long & faithful” service. Despite his concessions, Condon assured, Clay had nothing to worry about.21

The lack of written documentation further comforted Clay, who now rested at Ashland several hundred miles away from Charlotte. Without an extant document that stated that a promise of freedom was made by Condon, Charlotte Dupee’s claim was considered hearsay. It did not meet the evidentiary standard of the court raised by previous freedom suits in the District. Dupee’s claim that she had been promised conditional freedom crumbled.22

Dupee Minute Book Entry

O Say Can You See, National Archives and Records AdministrationAs he prepared for his next presidential campaign, Clay privately “waited with some anxiety” for a resolution to Dupee’s freedom suit. Finally, in May 1830, more than a year after filing, the court ruled against Charlotte Dupee, denying her petition for freedom. As a result, her legal protection in Washington, D.C., ceased. Nevertheless, she found new ways of resisting.23

Dupee exacerbated Clay’s anxiety when she refused to return to Ashland. Unable to persuade her to come back, Clay angrily ordered his agent in the city, Philip Fendall, to imprison Dupee for her “perverse or refractory disposition:”24

"Her husband and children are here. Her refusal therefore to return home, when requested by me to do so through you, was unnatural towards them as it was disobedient to me. She has been her own mistress, upwards of 18 months, since I left her at Washington, in consequence of the groundless writ which she was prompted to bring against me for her freedom; and as that writ has been decided against her, and as her conduct has created insubordination among her relatives here, I think it high time to put a stop to it…”25

The exposure of Clay’s anxiety, anger, and personal perspective is quite telling. Through the eyes of her enslaver, Charlotte Dupee broke every unwritten rule of their relationship by being “her own mistress” for eighteen months. Foremost, he explicitly indicates his view that by staying in Washington, D.C., after the case was decided, Dupee behaved “unnaturally” toward her family. With children and a husband at Ashland, Clay demanded that she resume her “natural” role as mother, caregiver, and wife. Additionally, her refusal to return coupled with the vacancy at Ashland of a domestic servant marked blatant disobedience in Clay’s view.26

And what result did her degree of independence yield? Strikingly, Clay admitted that Charlotte Dupee’s actions “created insubordination among her relatives” at Ashland. Although unable to obtain her immediate manumission, Dupee exhibited a model of expressed freedom for her enslaved community in Kentucky. This, perhaps, is the most emphatic consequence of Dupee’s freedom suit. To be sure, Charlotte Dupee’s resistance rattled Henry Clay and James Condon enough that they shared their fears in private correspondence. But her ability to incite “insubordination” among an enslaved community over five hundred miles away from Washington, D.C., signifies the magnitude of her actions in 1829.27

Birds’ Eye View Of New-Orleans. 1851.

The Historic New Orleans CollectionIn September 1830, Henry Clay proclaimed that it was “high time to put a stop” to Charlotte Dupee’s independence in Washington, D.C. He enlisted his administrator to arrange for Dupee to be jailed. While records of her imprisonment remain undiscovered, the reason she was detained is certain: Dupee flouted the commands of her enslaver. Clay and Fendall scrounged Washington for a slave trader or a ship that could transport the defiant Dupee back to Kentucky or possibly to Clay’s daughter in New Orleans. Eventually, the pair settled on the latter option. They dispatched Dupee via boat around the southeastern coast of the Atlantic, through the Gulf of Mexico, and into port at New Orleans. There, she found herself living in yet another culturally unique institution of slavery.28

New Orleans in the 1830s usually meant nightmarish prospects for enslaved people. But for Charlotte Dupee, it wasn’t the slave market that awaited her in Louisiana, but an extension of Henry Clay’s own plantation system. Dupee assumed a similar role in New Orleans for Clay’s daughter Anne Brown Clay Erwin as she had at Ashland—namely, wet nurse and caregiver for Henry Clay’s grandchildren. Anne Brown Clay Erwin wrote of the relationship between her daughter and Dupee in an 1832 letter to Henry Clay:

Aunt Lotty and her have at least a dozen quarrels of a day; I cannot thank my dear Mother enough for having spared Lotty to me, she is the best creature I ever saw and appears to be quite as much attached to the children as she ever was to yours. Tell Mama I shall certainly execute her commission with a great deal of pleasure...29

After caring for the Erwin children, Dupee eventually made her way back to Ashland under the supervision of Clay. It was there, on October 12, 1840, that he manumitted Dupee and her daughter, Mary Ann, effective immediately, "in Consideration of the long and faithful Service of my slave Charlotte and of her having nursed most of my children, and several of my grand Children." "But," the deed continued, "this deed is not Construed to Emancipate any of the Children of the said Charlotte and Mary Anne or either of them born prior to the execution thereof, the said Children so born before the present date remaining subject to me.”30

Charlotte Dupee’s freedom suit reverberated more than a decade after she filed her petition. According to her deed of manumission, all of the children born of Charlotte Dupee or Mary Ann prior to the manumission date remained Henry Clay’s property or “subject” to him. By adding this clause at the end, he put in writing what previous bills of sale lacked: explicit language documenting who was born of whom and the exact status of the mother’s freedom. Charlotte Dupee administered Henry Clay an embarrassing lesson in 1829. Though we do not know why Clay chose to manumit Dupee in 1840, his language signaled Dupee’s freedom petition changed Clay’s enslaving practices.

Charlotte Dupee did more than challenge Clay’s character and honor. When she refused to return to Kentucky, she not only defied her enslaver but also the social norms of slavery. Separated from her family and kin, Charlotte’s actions in Washington, D.C., incited sentiments of unrest among Ashland’s enslaved community some five hundred miles away. For over a year between February 1829 and May 1830, Charlotte was, indeed, “her own mistress.” Clay’s tone was entirely condescending, but the comment hinted at a deeper truth. Determined to become free, Charlotte fashioned a period of temporary independence for herself. In a very real way, Charlotte became a living example of freedom for the enslaved at Ashland. Her actions exposed the lie of Clay's paternalism and exhibited an attainable pathway to freedom for those in her social network and for those who followed in her footsteps.

William Kelly is a Ph.D. student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he studies the long nineteenth century and slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.