Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Decatur House Silhouettes

This article is part of the Slavery in the President’s Neighborhood initiative. Explore the Timeline

Through research and analysis of written accounts, letters, newspapers, memoirs, census records, architecture, and oral histories, historians, museum professionals, and descendants seek to restore the voices of enslaved people. Although it is possible to construct certain details of an enslaved person’s life, it is often difficult to know about their physical appearance because it is extraordinarily rare to find images, photographs, or drawings of these individuals. However, primary sources including emancipation records, physical descriptions, letters, and photographs of descendants can help historians and researchers envision what individuals might have looked like through artistic representation.

The White House Historical Association worked closely with artist Chris Danemayer and the Decatur House Advisory Council to create silhouettes representing three enslaved individuals that lived and worked at Decatur House: Charlotte Dupuy (also Dupee), James Williams, and Nancy Syphax. The Decatur House Advisory Council includes Nancy Syphax descendent and historian Stephen E. Hammond, curator at Henry Clay’s Ashland estate Eric Brooks, and historical archaeologist Julianna Jackson.

There are no known existing depictions of Charlotte Dupuy/Dupee, James Williams, and Nancy Syphax. The Association selected these three people to represent different time periods, ages, and lived experiences. Their silhouettes are now featured in the historic Slave Quarters at Decatur House as projections onto the wall. They offer an artistic representation of those individuals that lived and worked at Decatur House and provide additional information about the experiences of slavery onsite. In addition, these silhouette projections are featured on a new tour of Decatur House, which better incorporates the lives and stories of those enslaved in the home.

Charlotte Dupuy/Dupee

The White House Historical AssociationCharlotte Dupuy/Dupee was enslaved at Decatur House during Henry Clay’s tenure as secretary of state for President John Quincy Adams (1827-1829). As Clay prepared to return to Kentucky in 1829, Charlotte sued him for her freedom in the U.S. Circuit Court of the District of Columbia. Charlotte maintained that her previous owner, James Condon, had promised freedom for her and her two children. Instead, he sold them to Clay in 1806. As the court considered this case, Charlotte was allowed to remain at Decatur House where she worked for its new occupant, Secretary of State Martin Van Buren, while Clay, her husband Aaron, and their children returned to Kentucky. She eventually lost the case and Clay sent her to New Orleans where she was forced to work for Clay’s daughter. However, for unknown reasons, Clay manumitted Charlotte and her daughter Mary Ann in 1840. Clay also manumitted her son Charles in 1844.1

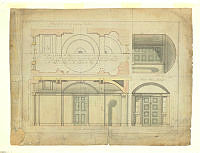

Charlotte and her family’s presence mark the first documented instance of enslaved people living at Decatur House. They likely lived in service wing, which had previously been used by the domestic staff of foreign ministers. The wing evolved into an urban slave quarters during Clay’s residency, and solidified as such during the ownership of John Gadsby. Born between 1787 and 1790, she was likely around the age of forty when she sued for her freedom. While working in Clay’s Decatur House alongside her husband and two children, it is likely Charlotte filled several roles, laboring as a cook, housekeeper, and possibly caretaker for Clay’s young children.2

Charlotte’s silhouette depicts her standing in profile with her hand outstretched holding a piece of paper. Although it is not known whether Charlotte was literate, the document represents her and her attempt at self-emancipation. While initially unsuccessful, her pursuit of freedom demonstrates her resolve and the different ways enslaved people used available resources to emancipate themselves.

James Williams

The White House Historical AssociationJames Williams was enslaved at Decatur House by enslaver and hotelier John Gadsby as a child. He appeared on an inventory taken after John Gadsby’s death in 1844 at the age of three years old, along with twenty other enslaved people, including six other Williams family members. A second inventory, completed in 1858 after the death of Gadsby’s wife Providence, records his age as sixteen-years-old. Notably, this second inventory only lists three members of the Williams family, as opposed to seven in 1844. This means that James Williams possibly experienced a painful family separation while living and working at Decatur House, a common experience for many enslaved individuals.3

Although details of his everyday life are not well known, aspects of his physical appearance were documented in his emancipation records. On April 16, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed an act which emancipated enslaved people in Washington, D.C., but also allowed slave owners to receive up to $300.00 in compensation for their loss of “property.” The petition for James Williams, submitted by Gadsby’s daughter-in-law, Mary Augusta Gadsby, described nineteen-year-old James as a “first class waiter, a superior cook, & a thorough house servant.” It also described details of his physical appearance: “black hair & eyes, thick lips, [a] gruff voice, and about five feet eight inches high.”4

In this silhouette, James is depicted as an enslaved teenage waiter, holding a soup tureen, and dressed in livery. The livery indicates Williams’s public role in the Gadsby household, likely serving guests in the dining room.

Nancy Syphax

The White House Historical AssociationNancy Syphax was also enslaved by John Gadsby. She appeared in Gadsby’s 1844 inventory at the age of forty-five. She appeared again in Providence Gadsby’s 1858 inventory with the listed age of fifty-five. Though many of her family members were freed by 1837 through the efforts of Nancy’s father, William Syphax, she remained enslaved until Washington, D.C. abolished slavery in 1862. Nancy’s petition, submitted by Gadsby’s daughter Augusta McBlair, describes her as “…about 5 feet 2 inches high, Yellow Complexion, Black eyes, grayish black hair, age 53 years & healthy…good nurse, house servant and laundress…”5

Nancy’s experience as an older enslaved woman is interesting because even after obtaining her freedom in 1862, she continued to work for Gadsby’s daughter, listed within the McBlair household in the 1870 census at the age of seventy-nine. Although it is difficult to determine Nancy’s reasons for continuing to work for her former enslaver, it was likely difficult for Nancy to find alternative employment to support herself at that age.6

Based on the description in her emancipation petition, the silhouette depicts Nancy ironing and hanging laundry at Decatur House. She is also shown wearing a headscarf. Although there are no known photographs of Nancy, her descendent Stephen Hammond provided a tintype photograph of Nancy’s daughter, Margaret Syphax, who may have also lived at Decatur House. Margaret was likely sold between 1830 and 1838 in Washington, D.C. or Alexandria, and taken to New Orleans, Louisiana. While it is unknown if Margaret was separated from Nancy and sold at Decatur House, Nancy is depicted working yet looking upward, contemplating her daughter’s fate. In this image, Margaret is seen wearing a head scarf, inspiring the inclusion of a head scarf in Nancy’s silhouette.

Stephen E. Hammond & Margaret Syphax

Stephen E. HammondThese silhouettes of Charlotte Dupuy/Dupee, James Williams, and Nancy Syphax are projected on the north facing wall of the historic slave quarters at Decatur House alongside a quote from Solomon Northup’s 1853 memoir, Twelve Years a Slave:

The voices of patriotic representatives boasting of freedom and equality, and the rattling of the poor slave's chains, almost commingled. A slave pen within the very shadow of the Capitol!

Originally born a free man in New York, Northup traveled to Washington, D.C. in 1841to play violin with a group of traveling musicians. Upon reaching Washington, D.C., Northup stayed at the National Hotel, where he was kidnapped, chained, imprisoned, and sold to slave trader James H. Burch. In his memoir, Northup describes his experience of being held in a slave pen. He points out the stark contrast between the nation’s lawmakers espousing ideas of equality and his position in a slave pen within the shadows of the Capitol, a symbol of American freedom and democracy. Northup’s words represent this reality for those enslaved in the nation’s capital and demonstrate slavery’s persistence within the President’s Neighborhood. This quote provokes further reflection on the paradoxical relationship between slavery and freedom in the nation’s capital.7