Restoring the Original White House Stone

Copyright © Spring 1998 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

The restoration of the exterior of the White House, which I performed from 1989 to 1996, was an exciting and challenging task. Dealing with a building of this historic importance added another dimension to my responsibility, and it was with great respect that I strived to uphold the standards of the work of the Scottish masons who originally built this unique mansion. As an English mason trained in a traditional apprenticeship system, and with over thirty years of experience in the restoration of historic buildings, I was able to continue the unbroken tradition of stonemasonry in which those Scottish masons worked 200 years ago, with the help of modern-day tools and materials. In this article, I will share with you some of those procedures and traditions I undertook during the restoration.

The areas of greatest deterioration were the course, or layer, of stones that form a projecting molding above the ground-floor windows and many of the stones in the entablature, which comprise the cornice, modillion, dentil, frieze, and architrave stones. These areas were more affected than the flat ashlar walls because they are small projections, which are much more vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the weather. Most stones are broken down by wind, rain, and the freeze/thaw cycle.

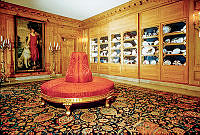

This black and white photo shows the stone swag above the north entrance during a maintenance project.

White House Historical AssociationIron cramps are another source of stone failure. Their original purpose was to tie one stone to another, locking the stones tightly together, end to end. On the west side of the south elevation of the White House, there were at least six cramp failures, most of them in the dentil course. Cramp failure begins when the iron is exposed to moisture, through an open joint, a crack, a puncture or separation in the lead or copper flashing, or simple weathering. When the iron rusts, it expands, exerting tremendous pressure within the stone. To release this pressure, the stone will crack, either into a joint or through the face of the stone, as these are the two places of least resistance.

Thermal expansion and contraction (the warming of the building in summer and the cooling in fall and winter) account for still more cracking. This is very evident on the south and west elevations, where old cracks can be seen going down through and past the entablature. Over the years, attempts have been made to fill the cracks, and every year they open up again, fragmenting more stone away from the area. When replacing a run of dentil stones through this area, it is important to remember to treat a crack as a joint, and not merely to span it with a new stone, or the crack will reappear in precisely the same place, ruining the new stone. The modillion and dentil courses were the worst affected in the entablature, with large areas of stone missing. To preserve the outline of the dentils and cover up the decay, a previous restorer had encased individual dentils in cunning little copper boxes, which, when painted, looked close enough to stone to fool the average onlooker. I unscrewed the boxes from the wall only to find the merest vestiges of what were once crisp outlines. Above the dentil course, the modillions (which cantilever out to help support the cornice stone above) had been given the same copper-box treatment. The task was to reproduce the original dimensions and details of both, using the same Aquia Creek sandstone that the Scottish masons had used 200 years before.

A detail of the stone swag above the north entrance during the restoration process.

White House Historical AssociationThe process of selecting stone for the restoration began in the Rock Creek facility of the National Park Service, where tons of blocks of sandstone are stored. Aquia Creek sandstone is not famous for its quality, so I carefully examined each block for its faults (i.e., hairline cracks, pebbles, large clay nodules, and fossilized vegetation). After finding a sound block, I selected the piece for its color and texture (how fine or how coarse the stone is). This plays an important part when matching the stone with the original stone on the building. The stones were then hauled into the sawing shed, where they were cut into the appropriate sizes by an electrically powered forty-eight-inch diamond circular saw blade.

Once the stones were sawed into basic blocks, they were taken to the White House stone shop. Before commencing cutting of any stone, I first made a pattern, or template, in order to give me an exact profile of the molding. Then I calculated the balance point, which is the distance from the wall line to the farthest point out on the face. By squaring the wall line from the bottom of the template to the top, I then determined how much I needed to add or subtract to make the template balance. This gave me the depth of stone I would need to replace in the wall.

A mason’s mark is a trademark unique to each mason or stonecutter. Since the mark is normally cut on the top or bottom of the stone, the only person who would ever see it is another mason performing restoration work.

Though stones today are shaped with the aid of pneumatic air hammers, the contour of the hammer’s chisel tip has remained unchanged for centuries. Using the air hammer, I followed the lines of the template, cutting away the stone until the levels corresponded to the various heights of the pattern. After each large stone was finished, I or one of my assistants would carve our personal mason’s mark into its top bed. A mason’s mark (or banker mark) is a trademark unique to each mason or stonecutter. Since the mark is normally cut on the top or bottom of the stone, the only person who would ever see it is another mason performing restoration work by removing the stone above or beneath it. There was always great interest among my crew when someone was cutting out a stone to see the cutting slowly reveal the mark of the mason who had worked the stone 200 years before. Upon uncovering an original mason’s mark, I notified the Office of the Curator at the White House so that the mark could be documented before the area was covered up again.

The next part of the restoration involved mapping out the decayed areas of the stone, which were to be removed. In some areas, I had to remove a six-to-ten-foot run of dentil stone. Some of the old dentil stones are eight feet long, and it would have been so simple just to cut the whole stone out and replace it with a new one. But a mason must always remember to support the weight of masonry above the area being removed. So instead, I divided the area being removed into four, and cut four replacement stones. In that way, I could cut out stones number one and three while numbers two and four were supporting the weight of the stone above.

To set these large blocks into their individual positions, the stones were hoisted from the ground to the top of the scaffold by the use of a chain fall. The wall and the stone were then measured for corresponding dowel holes. Threaded dowel pins of stainless steel were cut and placed into the back and sides of each stone to lock it in place. The stone was then positioned onto a wooden plank that had been sprinkled with fine sand (which acts like ball bearings) and slowly pushed into the wall. Once a stone is in the wall and lined up with the stones on either side, the joints and beds can be pointed up and left to dry for an hour. A bucket of grout (liquid mortar) is mixed up and poured through the opening at the top of the joint. The purpose of the grout is to fill all the voids in and around the stone. Once the grout has dried, the stone is locked into the wall.

A view of the column capital on the south porch of the White House.

Library of CongressFor small repairs on the building, I fashioned what masons call “dutchmen,” which are small replacement stones. First, the affected area is cut out to a depth of four inches. All edges must be square and true, and the front lines are hand- rubbed. Time and care are taken to select a stone (the dutchman) that matches as closely as possible the color and texture of the original. The dutchman is cut to size and hand-rubbed to achieve a hairline fit. It is then given an application of epoxy resin and pushed into place. Care must be taken not to smother the piece with epoxy, but to leave open areas so that the dutchman can breathe.

In summary, my restoration method combined centuries-old techniques with modern materials to achieve a lasting quality which I hope will serve the nation’s most prestigious house for centuries to come.