Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Monuments to the American Revolution in Lafayette Park

Lafayette Monument, Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C.

Library of CongressIn 1853, Clark Mills’ statue of President Andrew Jackson on horseback is in the center of Lafayette Park. The park’s four corners were later allocated for statues commemorating significant Europeans who assisted American forces during the American Revolution. In 1891 the first statue was erected, honoring the Marquis de Lafayette. Some feared the statue would impact the view of the White House in relation to the existing statue of Andrew Jackson. After much discussion, the southeast corner of the park was chosen as the appropriate location for Lafayette. In March 1951, visiting French President Vincent Auriol laid a wreath at the Lafayette statue.1

Rochambeau Monument, Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C.

Library of CongressOn May 24, 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt spoke at the dedication of another statue, this time placed in the southwest corner of the square. Fernand Hamar’s monument honored the Comte de Rochambeau, whose leadership was crucial to the American victory over the British at the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. A symbolic confirmation of French-U.S. ties, the statue’s dedication received much attention in the press. During his speech, President Roosevelt noted the crucial relationship between France and the United States, speaking to the French diplomats assembled, “because the history of the United States has been so interwoven with what France has done for us . . . the American people, through me, extend their thanks to you.” As the statue was unveiled, the Marine Band struck up “La Marseillaise.”2

Kosciuszko Monument, Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C.

Library of CongressA statue by Antoni Popiel commemorating General Tadeusz Kosciuszko, a Revolutionary War hero from Poland, was dedicated on May 11, 1910 in the northeast corner of the park. That same day, a statue to another Polish hero of the American Revolution, Casimir Pulaski, was also dedicated in Washington, D.C. at 13th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, Northwest, several blocks from Lafayette Park. President William Howard Taft appeared at both dedications. At the dedication of the Pulaski statue, President Taft summarized the significance of these statues to European military heroes in Washington D.C., saying, “It is idle to speculate what might have been the success of American arms in the war of the revolution had we not been assisted by foreign nations and subjects of foreign countries. It is sufficient for us to note that those who assisted us in that struggle for independence and liberty contributed materially to our success . . . it is fitting that there should be erected monuments like this, to have it understood that America is grateful and holds in sweet memory those who came to her, in her hour of danger and of trouble.” 3 This dual celebration drew thousands of Americans of Polish heritage to the dedication ceremonies. 4

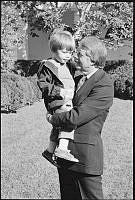

Helen Taft and her father, President William Howard Taft, at the dedication and unveiling of the von Steuben Monument in Lafayette Park on December 7, 1910.

Library of CongressThat December, on a sunny day when snow lay on Lafayette Square, the final statue was dedicated on the northwest corner. German ambassador Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff was present at the ceremony, as Albert Jaegers’ bronze sculpture honored Prussian-born Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who assisted in training American troops during the Revolution. President William Howard Taft spoke at the dedication and his daughter, Helen Taft, unveiled the statue. 5 President Taft told the assembled crowd, “We dedicate today the last of the monuments which fill the four corners of this beautiful square and which testify to the gratitude of the American people to those from France, from Poland and from Prussia who aided them in their struggle for national independence.” After the dedication, local and visiting German-American organizations hosted banquets across the city. Even the German press in Berlin covered the event, publishing President Taft’s address. 6

Together, these statues commemorate the significance of the European military leaders who helped the United States win independence from Great Britain.