In a White House Passageway

Evidence Survives of James Hoban's Building Skill

Copyright © June 01, 2011 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

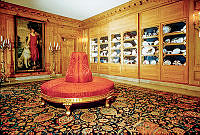

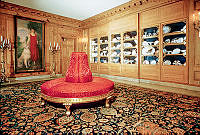

Located beneath the South Portico, this vestibule most clearly illustrates the system of vaulting James Hoban devised for the 1824 addition. The groined arch forming the ceiling of the vestibule makes the tall doors possible by redirecting the weight borne by a low-slung barrel vault that supports the heavy stone floor of the semi-circular South Portico above.

Arches and vaults are techniques of construction that serve to divert the support of heavy masses that would otherwise require bearing walls or pillars directly beneath them. They have been in use for millennia, forming the structural systems of buildings. Steel beams in the later nineteenth century rendered vaults and arches unnecessary, and indeed generally replaced them. James Hoban built the White House according to the only systems he knew, which included arches and vaulting. When President Harry S. Truman renovated the building from 1948 to 1952, he built it back with modern steel. Although vaulting was no longer necessary with the new system of steel beams, the original was nevertheless suggested in plaster, to look as it always had. Vaulting is striking to see, of course, but its true beauty lies in its utility.

In two parts of the house the bulldozers of the 1950s made no mark. The North and South Porticoes were unchanged. Their vaulted supports remain as Hoban built them, that on the South in 1824, and the North Portico between 1829 and 1831. The structural preciseness of the groin vaulting shows Hoban’s creative intellect as an engineer.

James Hoban won the competition for design of the President’s House in 1792 and had overseen its construction until 1803, when President Thomas Jefferson replaced him with Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Hoban was subsequently rehired in 1815 to rebuild the White House, after the invading British Army burned the building in the previous year. Hoban incorporated such remains of the original as he was able to, but almost all these elements of his earliest work and subsequent reconstruction were lost during the comprehensive Truman-era rebuilding. Yet Hoban’s engineering remains in the porticoes, both of which are underpinned with adapted groin vaulting to suit peculiarities of form and situation. These are among the only historic structural systems still performing their original job in the Executive Residence.

Diagram of a barrel vault

The intersection at right angles of two barrel vaults forms a groin vault

Finished in 1824, the rounded South Portico was a near-perfect addition to the river face of the White House. With a full width of 61 feet, the portico gave visual focus to the 168 foot expanse of the south elevation. It created a protected extension, a terrace or viewing platform, for the state parlors, as well as a serviceable entrance by means of an elegant double flight of stairs, rising almost 13 feet from the ground.

The South Portico is defined by six Ionic columns that step out and around the center bow or bay, as a fully three-dimensional continuation of the monumental “pilastrade,” or row of pilasters, that rings the house on three sides. Like the pilasters, the columns of the portico are raised on square plinths. The shafts are Seneca sand- stone, made in sections and pinned at their centers with iron. They are smooth, in contrast to the heavily rusticated treatment of the Ground Floor wall where the portico base, extending outward, becomes a high podium. Seven arched openings pierce the thick walls of this podium, providing the only outward expression of Hoban’s groin vaults, which support the portico.

A groin vault is formed when two barrel or “tunnel” vaults cross. The name is derived from the arcing edge produced at the intersection of the vaults, which is called a “groin.” In a perfect crossing, the groins define four equal-sized wedges that are the vault. Each of these elements is known as a “groined arch.” When used in small spaces, groin vaults sometimes have a dome-like quality, a loftiness that can belie dense masonry construction.

South Portico: A section and axonometric diagram of the South Entrance vestibule after sketches in the HABS field notes for the White House. The section conveys the irregular nature of the vaulting in this space. Because the top of the groined arches, over the interior and exterior door openings, do not meet the top of the barrel vault at the same height, a true groin vault is not formed. Hoban corrected a difficult situation with masterful adaptation.

Why did Hoban trouble himself to build vaults for a more or less self-supporting addition like the portico? As with the original Ground Floor corridor, the vaults of the portico were intended to most efficiently direct the weight of the First Floor’s stone pavers. They also added assurance that the large addition would not compromise the physical integrity of the load-bearing walls of the residence. For both practical and aesthetic reasons, the vaults under the portico floor were a non-negotiable part of Hoban’s design. A solid base would have been materially wasteful and structurally unnecessary in addition to eliminating because of sheer bulk any ground-level access to the residence. The openings behind the seven archways lightened the heavy mass of the portico and also established visual interest, giving an element of shadowy depth to contrast with the out- ward curve and dramatic rustication of the podium. Hoban crafted these voids with a series of groin vaults and groined arches.

Vaulting is visible in six of the seven bays at the South Portico, while a modern dropped ceiling covers visible evidence in the seventh. Now used for an interior vestibule, the center bay most legibly conveys the manner in which Hoban conceived the vaulting system and some of its quirks.

A transverse, north-south, section through the residence and Ground Floor plan indicates that the groin vault that arches over the space is in fact irregular. It might even be better described as a barrel vault intersected by two groined arches, as the north-south vault is smaller than the east-west one. consequently, the north and south groined arches can never fully intersect.

The complex vaulting beneath the South Portico is testimony to Hoban’s skill. Here he tailored conventional forms of groin vaulting to the extraordinary needs of the curving South Portico. Though irregular in form, his vaults still perform their primary function in shouldering and transferring weight safely through the arch to the wall. The barrel vault extending east to west, following the curve of the portico, effectively carries the compressive weight of the upper portions downward. Groined arches intersect this semicircular vault over each of the openings, redirecting the outward and down- ward thrust around them. Hoban used the resulting groin vaults for bays with an exterior opening for each. The remaining interior bays were firmly fixed on the solid south walls of the house and required only a single groined arch over the doorway. Portions of the vaulting were obscured when the outermost bays were enclosed as rooms, but the doorway part remains exposed.

Section through the segmental vault supporting the areaway bridge on the north side of the White House, created byBenjamin Henry Latrobe in 1807–8. James Hoban extended the vault one bay to the east and one to the west in1829–30 to support the North Portico. The shaded area on the left of the image marks the groined arch used to direct the downward thrust of the vault around a door opening in the north wall. When he expanded the vaulting, Hoban replicated this structural feature for the two windows flanking the door.

Five years after the 1824 completion of the South Portico, Hoban was called back to build the North Portico on the Pennsylvania Avenue side of the house. Here a modest vault already existed, a narrow, single span built by Latrobe for Jefferson to support a bridge over the north areaway or light well to the front door. Hoban’s challenge was therefore less complex than with the South Portico. The sharp decline in the White House grounds from the north or Pennsylvania Avenue side to the south necessitated the areaway, so that the basement’s kitchens and service rooms would have natural light and ventilation, sunk as they were some 12 to 13 feet below grade on that side.

In 1807–8, Latrobe’s new bridge was an elegant, well-made addition to the President’s House and is still part of the support of the great North Portico. Latrobe’s broad segmental vault, made of brick faced on the east and west sides with stone to match the house, is still visible. A groined arch over the lower door—the kitchen door—joined engaged buttressing that flanked it to dis- tribute the load of the heavy masonry bridge above. The north end of the vault required no groining, for it met a “pier” formed by a small storage room of brick and rubble built into and extending into the earth beyond the stone retaining wall of the areaway.

In enlarging the bridge to serve the new portico in 1829, Hoban merely duplicated the segmental vault one bay to the east and one to the west, using an essentially identical arrangement of groin arches to clear the windows flanking the kitchen door.

Although the full arc of the vault under the North Portico remains visible, twentieth-century partitions obscure much of the underlying structure. Late in 2006, the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) of the National Park Service had the opportunity to document a segment of this vault. Fortunately, the area recorded by HABS contained part of Latrobe’s central vault with its stone facing with Hoban’s duplicate work beyond. This was a rare and welcome opportunity to see the construction methods and materials that have provided the grand North Portico a stable foundation for the better part of two centuries.

View of the Latrobe-Hoban segmental vault under the North Portico. The course of cut stone that formed the outer edge of Latrobe’s original vaulted bridge still reads clearly as a broad rectilinear rib arcing gently downward (northward) toward the rear of the space. Both the Latrobe (left-west) and Hoban (right-east) brick vaulting on either side is composed of three courses of stone at the point where it meets the rear wall, followed by neat brick courses laid in English bond, presumably returning all the way back to the residence. In total, this vault has supported the North Portico for nearly two centuries.

About HAbS

The Historic American Buildings Survey

The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) is the nation’s first federal preservation program, begun in 1933 to document the nation’s architectural heritage. It is among the last surviving agencies of the New Deal. The originators of HABS were motivated primarily by the disappearing man-made landscape and the monuments of architecture that seemed threatened by progress. Architects interested in the colonial era had previously produced drawings and photographs of historic architecture, but only on a limited, local, or regional basis. In the tripartite agreement that designed HABS, including the American Institute of Architects, the Library of congress, and the National Park Service, groundwork was laid for a far more comprehensive approach. Today HABS is still vigorously adding to its massive collection at the Library of congress, which includes measured drawings in ink, large-format photographs, and written histories. The collection was purposefully designed to include all aspects of the built environment whether locally, regionally, or nationally significant, both vernacular and, as with the White House, high style. Buildings recorded by HABS can be seen on the Library of congress website and the collection itself is available to the public.