Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Coffee and the White House

Coffee is a major global commodity that has shaped the lives of countless people throughout history. It is a beverage with multiple meanings and uses, the most common being its role as an energy stimulant and signifier of social habits. An examination of eighteenth and nineteenth century coffee consumption at the White House demonstrates how coffee became an important part of early American social and consumer culture.

During the early 1700s, colonists expressed a fondness for tea, which reflected their colonial heritage and identity. The American War of Independence marked a critical turning point as the colonies turned away from teahouse culture giving way to coffeehouses. During this period, coffee became a revolutionary drink as it publicly signaled one’s political inclinations. After the war, consumers developed an affinity for both coffee and tea. The connection between coffee consumption and the President’s House in early United States history is evident during the administrations of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century presidents such as George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. The paths by which coffee entered the President’s House involved enslaved laborers who cultivated coffee in the Caribbean, servants, and eventually, the Executive Mansion’s occupants who consumed it.1

Arbre du café dessiné en Arabie sur le naturel

Library of CongressDuring the eighteenth century, coffee arrived in the colonies through a growing transatlantic trade network. In the New World colonies, the Dutch were responsible for the circulation of arabica coffee beans from Ethiopia ca. 1650, thus beginning the incorporation of coffee on seventeenth-century plantation systems.2 In Dutch colonies such as Suriname, enslaved laborers, primarily from the west coast of Africa, cultivated coffee among other export commodities such as sugar, cacao, and cotton. In 1728, Britain introduced coffee beans to Jamaica where they were also cultivated by enslaved Africans, and soon after, coffee became a staple commodity in British Atlantic trade. Although widely available in the early eighteenth century, coffee had not yet risen in popularity to the level of tea. The coffee consumed during this time was not always the most delectable. For example, on February 15, 1760, George Washington recorded in his diary that he attended a ball in Alexandria, Virginia, where coffee was served which “the Drinkers of coud not Distinguish from Hot water sweetned.”3 Aside from the skill required to make flavorful coffee, its beans required special grinding equipment.4 Coffeehouses, thus, became the most common places for coffee consumption and were central to male socialization and political dialogue.5 Coffeehouses during this time also catered to the needs of merchants and traders by acting as centers of commerce for those seeking to purchase or sell goods such as coffee beans. They also provided services such as banking, maritime insurance, and public securities. During the 1780s, as these services developed into distinct industries, coffeehouses would adapt to become more like taverns and inns. Coffeehouses began providing drink and food items including coffee and chocolate as well as social and intellectual spaces.6 These were the places for discussions on politics, society, Enlightenment ideals---incubators of revolution.

Exchange Coffee House, 1-5 Market Square, Providence, Providence County, RI

Library of CongressBefore becoming the second president of the United States, John Adams viewed coffeehouses as social and political spaces. Writing to James Warren, Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives (1787-1788), on October 7, 1775, Adams stated:

…the Debates, and Deliberations in Congress are impenetrable Secrets: but the Conversations in the City, and the Chatt of the Coffee house, are free, and open. Indeed I wish We were at Liberty to write freely and Speak openly upon every Subject, for their is frequently as much Knowledge derived from Conversation and Correspondence, as from Solemn public Debates.7

Coffeehouses were spaces for men across social classes to engage in intellectual discussions and debates, but due to the gender conventions of the time, coffeehouses often excluded women.8 Adams’ contemporaries, including Benjamin Franklin, frequented coffeehouses where they discussed early colonial politics.9

During the 1760s, tensions grew between the American colonies and Great Britain regarding the former’s reluctance to pay taxes on several types of goods—such as molasses, sugar, paper, and tea—leading colonists to protest these policies and demand proper representation in Parliament. This dispute led to the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, in which colonial patriots threw several hundred cases of British East India Company tea into the Boston Harbor.10 This marked the beginning of a cultural shift away from tea in the colonies. Parliament retaliated by passing the Intolerable Acts, which involved closing the Boston Port until the colonists paid for the destroyed tea. In light of the economic warfare between the colonies and Great Britain, to drink tea in Massachusetts, specifically and throughout the colonies generally, would have signaled one’s political loyalties in public.

Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor

Library of CongressThe following year, John Adams began drinking coffee every afternoon and stated, “tea must be universally renounced… I must be weaned, and the sooner, the better.”11 Although colonists paid import duties on coffee, tea more directly symbolized British culture. By distancing themselves from tea in favor of coffee, colonists demonstrated their political, economic, and social distinction from the British and began forging separate cultural identity around this beverage.12 These tensions climaxed with the outbreak of the American War of Independence (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783). When colonists altered their drinking habits in symbolic pursuit of American independence from Britain, they paved the way for a thriving coffee consumer culture that penetrated every level of society, even reaching the President’s House.

Various newspaper accounts indicated a popular fascination with coffee as many sought to learn the origin of the beverage, its qualities, and effects on the human body.13 According to a 1786 Philadelphia newspaper, one correspondent detailed his prediction that coffee would “diffuse itself among the mass of the peoples, and make a considerable ingredient in their daily influence.”14 Coffee was also used medicinally to relieve headaches and aid digestion.15 Writing in 1788, the author of the newspaper article stated, “I have observed…that the use of coffee has increased from year to year, day to day, and is still becoming more general; insomuch, that the coffee planter need be under no fear or apprehension of failure in market or consumption.”16 As coffee was imported in greater quantities from the Caribbean during the early 1800s, more coffeehouses were opened throughout the country, primarily in the northeast.17

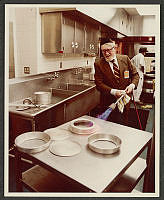

Adams’ tea or coffee urn

White House Historical AssociationAt the turn of the century, after twenty-five years of American independence, tea became less associated with pro-British loyalties and thus, re-incorporated into the American palate. According to the minutes from the proceedings of the House of Representatives on March 16, 1802, certain representatives expressed that while neither coffee and tea were “necessaries of life, they were consumed by the citizens generally in proportion to their wealth.”18 The redefined relationship with tea was not only reflected among average Americans, but was also evident in presidential consumption patterns. The beverages’ popularity at the President’s House mirrored the norms of etiquette and hospitality, and consumption habits for coffee among ordinary Americans.

Following the American War of Independence, President George Washington and First Lady Martha Washington served coffee alongside tea and lemonade at social gatherings hosted at the President’s House in New York, New York and later, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.19 Following his second term, George Washington returned to his Mount Vernon estate where he first received coffee plants from his grandson-in-law, Thomas Law, in 1799.20 The coffee was grown and prepared by enslaved workers at Mount Vernon and typically served alongside cakes and candied sweets during the winter season at the first lady’s levees.21

When John Adams moved into the President’s House in Washington, D.C. on November 1, 1800, he brought with him his affinity for coffee and renewed attitudes toward tea.22 Although Adams reincorporated tea into his diet after the war, he had grown to prefer coffee.23 The centrality of these beverages in everyday life is evidenced by material culture. Adams owned a silverplate neoclassical vase-shaped urn made by English silver manufacturer Sheffield during the 1780s.24 This urn, engraved with the president’s initials, was most likely acquired during Adams’ diplomatic trip as U.S. minister to Britain (1785 - 1788). Although the urn was intended to serve tea, Adams—a known coffee advocate—may have used it for coffee.25 The re-purposed use of the urn indicated a broader societal practice in which British traditions were adapted to fit an American context. Moreover, it suggests that while Americans embraced coffee as a form of resistance in the 1770s and 1780s, tea was not completely rejected but rather existed alongside a desire for coffee after the American War of Independence. Perhaps the Adams coffee/tea urn, which he may have brought to the President’s House, is an appropriate metaphor for American taste.

Bank Draft for Coffee Shipment Ordered by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson Papers at the Library of CongressDuring the early 1800s, green coffee beans were most common in America. Thomas Jefferson, however, preferred “the genuine well ripened coffee” of the Caribbean.26 Having spent considerable time at coffeehouses in Paris, France, Jefferson incorporated coffee as an essential part of White House dining.27 In the Jefferson White House, enslaved African Americans were forced to labor alongside free African Americans and white servants to fulfill everyday household tasks. Traditionally, kitchen staff provided coffee and tea to guests in the oval drawing-room, today’s Blue Room, following dinner.28 Among the kitchen staff was a scullion named Sandy, who was most likely a free African-American man. The president paid Sandy ten dollars per month.29 Sandy’s primary responsibility was supplying charcoal for the stew-stove where coffee was brewed.30 Such duties were essential to providing Jefferson with the drink he described as “the favorite beverage of the civilised world,” and which allowed him to maintain a level of social prestige the beverage signified.31

Before moving to the nation’s capital, James Madison and Dolley Madison regularly enjoyed breakfast at nine in the morning which consisted of “ham or salt fish, herring,…coffee or tea, and slices of toasted or untoasted bread spread with butter.”32 The Madisons continued their tradition of serving coffee alongside pastries at social gatherings to the White House in 1809.33 Through Dolley’s hospitality, she ensured that the White House was a place of lively political discourse for visiting guests. Dolley hosted levees featuring live musicians where enslaved African-American servants provided guests with coffee and tea, wine, and other refreshments.34 Additionally, the Madisons held large dinners for invited diplomats and government officials across party lines.35

After British troops set fire to the President’s House on August 24, 1814, the Madisons moved to a house on the corner of 19th St and Pennsylvania Avenue in March 1815, where they remained for the duration of the presidency.36 Here, Dolley continued hosting levees. Paul Jennings, an enslaved African-American man, was likely tasked with setting the tables and serving refreshments during the levees both at the President’s House and their new residence.37 Before leaving office in 1817, Dolley organized her final Wednesday evening reception, which had become the talk of the town. Coffee, punch, and wine were served to congressmen, foreign ministers, and employees of lower-ranking government offices.38 Throughout their time in Washington, coffee was a central component of social gatherings and daily consumption habits.

Coffee House Slip, New York 1828

Library of CongressThroughout the presidencies of George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, coffee was an essential beverage that enhanced and complemented the social spaces of the president’s personal estates and the White House. America’s earliest presidents participated in coffeehouse culture and reflected popular coffee consumption habits. As a newspaper correspondent summarized in March 1826, “There is, perhaps, no place where a man of the world can feel himself so perfectly at home as in a coffee-house.”39 Across the country, coffee houses were places where one “may get a cup of hot coffee or tea at any hour of the day,” thus catering to the American tastes by serving both beverages.40 In the legacy of the American War of Independence, the active embrace of coffee demonstrated political ties and coffeehouses facilitated the affiliated social culture. As tensions eased between Britain and the United States, Americans began incorporating tea back into their diets. This was reflected in the President’s House as well as in the daily consumption habits of average Americans who had come to balance their palates between both tea and coffee.