Rubenstein Center Scholarship

A Duke at the White House

Duke Ellington's Presidential Medal of Freedom: April 29, 1969

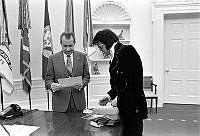

President Richard M. Nixon presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Duke Ellington in the East Room of the White House on April 29, 1969.

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum/NARAPresident Richard Nixon appreciated the cultural significance of music and how its composition encouraged creativity and self-reflection. In his memoirs Nixon noted that “playing the piano is a way of expressing oneself that is perhaps even more fulfilling than writing or speaking. . . I think that to create great music is one of the highest aspirations man can set for himself.”1 On April 29, 1969, President Nixon recognized this form of expression when he presented Duke Ellington with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, while celebrating the musician’s 70th birthday. The event was not Ellington’s first encounter with the White House and its distinguished occupants. Earlier in his career, the musician and band leader had sent President Harry S. Truman a personalized score; it was performed at a White House Correspondents dinner during the Eisenhower administration, the White House Festival of the Arts in June 1965, and a 1968 State Dinner.2

Ellington’s birthday dinner in 1969 featured Coquille of Seafood Neptune and Roast Sirloin of Beef Bordelaise, served in the State Dining Room.3 In his remarks, President Nixon noted that Ellington’s father had previously served as a butler in the White House for part of his life, and concluded with the humorous quote that although many heads of state had been honored, “never before has a Duke been toasted. So tonight I ask you all to rise and join me in raising our glasses to the greatest Duke of them all, Duke Ellington.”4

The event program for the Presidential Medal of Freedom event for Duke Ellington in the East Room of the White House on April 29, 1969.

Courtesy of Henry & Carole Haller and FamilyAfter dinner, guests moved to the East Room where Nixon presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the first of his administration, to Ellington with his family in attendance. After the ceremony, Nixon declared that he had not yet played piano in the White House and asked those present to join in a rendition of “Happy Birthday” for Duke Ellington, with the president on piano.5 A guest afterwards acknowledged Nixon’s musical ability saying, “He’s a good musician. I didn’t know that. He’s something else.”6

Musical luminaries in attendance, described by jazz producer and event emcee Willis Conover as “without exception among the very finest playing in the American musical idiom,” included music legends Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, and Earl Hines. It is thus no surprise that a celebratory jam session broke out after the evening’s formal concert of Ellington songs played by musicians such as saxophonists Paul Desmond and Gerry Mulligan, trumpeter Clark Terry, and drummer Louis Bellson. The session lasted until the early morning.7 Among the many jazz songs performed that night included an improvised piano number called “Pat” in honor of First Lady Patricia Nixon.8 When the event finally concluded, one musician summarized the festivities by commenting, “Man, this was some kind of great.”9 In January 1970, Mrs. Nixon appointed Willis Conover chair of a commission directing the expansion of the White House record collection. Conover also served as commission’s jazz specialist.10

Nixon cherished the Ellington event at the White House for the rest of his life. Upon the death of the jazz great in 1974, Nixon asked singer Pearl Bailey to be his personal representative at the Duke’s funeral and released a statement that “the wit, taste, intelligence, and elegance that Duke Ellington brought to his music have made him, in the eyes of millions of people both here and abroad, America's foremost composer. We are all poorer because the Duke is no longer with us.”11

President Richard Nixon and Duke Ellington together at the piano in the East Room of the White House. The piano was given to the White House by Steinway in 1938, replacing an earlier piano from 1903.

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum/ NARA