Unbuilt White Houses of the 19th Century

Copyright © February 5, 2015 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, several major proposals were made to alleviate crowding at the White House by erecting a new residence for the president and converting the old building to office and ceremonial use. A new mansion would also relieve concerns for the president's health. Tiber Creek had been walled and deepened early in the century, becoming the slow-moving Washington City Canal. In the summer the stench, insects, and miasmic heat and humidity from stagnant marshes in the environs of the White House was intolerable and considered to be a cause of fevers and waterborne illness.

In 1866, a Senate Resolution tasked the Secretary of War to survey and map certain tracts of land adjoining this city for the purposes of a public park and also a suitable site for a Presidential mansion. Nathaniel Michler, a major in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, completed this survey and submitted a report to Congress advocating the creation of a public park in the Rock Creek Valley, and proposing several new sites in higher elevations surrounding the city for the Executive Mansion. President Andrew Johnson approved plans to build an entirely new presidents house in what is now Rock Creek Park as early as 1867. However, Congress did not provide the funding.

The White House viewed from the south, ca. 1866.

A New House Proposed and a Grand Plan

President Ulysses S. Grant, inaugurated on March 4, 1869, had no real interest in a new White House and was content to make the historic White House more livable. President Chester Arthur pressed for a new house in 1881, but had to settle for a refurbishment of the staterooms by Louis Comfort Tiffany. The presidency celebrated its centennial in 1889, and the new First Lady, Caroline Harrison, began to develop ideas for an ambitious White House project to mark the anniversary. Architect Frederick D. Owen, a civilian employee of the U.S. Army, illustrated her plans to alleviate the overcrowded living space for the Harrisons and their relatives and to improve the White Houses cramped dining, reception and household maintenance areas.

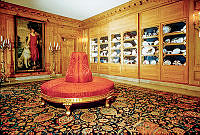

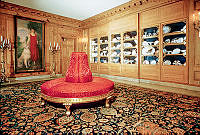

George Inslee's proposal for a private residence in 1881 for President Chester Arthur.

Mrs. Harrisons most ambitious conception would have extended the original house southward by adding a historical art wing facing the Treasury Department to the east, and an official wing facing the State, War and Navy Building to the west. Glass-enclosed palm gardens, plant conservatories and a lily pond would complete the southern portion of the quadrangle, which would be linked by two-story connectors, colonnaded cross halls and large glass domes to enclose a private inner courtyard.

Even with strong political support and a shrewd public relations campaign that garnered favorable press, Mrs. Harrison's plan foundered in Congress. For the next decade, the subject of the need for a White House expansion intrigued both presidents and their building commissioners. The campaign for an expansion culminated within a contest of civic improvement projects for Congressional approval to commemorate the centennial of the nations capital in 1900.

The Bingham Plan

On December 12, 1900, the City of Washington celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary as the seat of the federal government and the home of the president. The centennial of the first occupancy of the White House by President John Adams was observed with a great reception at the White House, a parade to the Capitol and observances by both houses of Congress. A centerpiece of the White House reception was a large plaster model of a plan developed in 1900 by Army engineer Colonel Theodore Bingham, superintendent of public buildings and grounds, to expand the White House.

North and South views of proposed additions to the White House, 1890. Drawings by Frederick Owen, architect.

The model revealed plans to replace the crowded working spaces with new offices, public and entertaining spaces and press rooms by constructing massive, flanking two-story cylindrical wings with domes and lanterns patterned after those at the Library of Congress. Bingham set up his model in the East Room and, after the president viewed the display and greeted the guests, rose to present a history of the White House that evolved into a sales pitch for the expansion. Roundly criticized by the architectural profession, the project stalled and after President McKinley's assassination awaited a new chief executives decision.

Congressional approval in 1902 of what was called the Roosevelt Restoration witnessed implementation of several concepts of the Harrison and Bingham plans, if not their details. President Theodore Roosevelt selected the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White to complete a renovation of the house that led to major changes in the interior and in the functioning of the building. During much of the nineteenth century the executive offices occupied the east half of the second floor leaving only the rooms of the west side and central hall as private family space. McKim doubled the space allocated to the family living quarters, provided a new wing for the president and his staff and included a new area on the east for receiving guests. The White House and, with a few exceptions, much of the complex we know today reflect the design of 1902 that preserved the White House as the home of the president.

The 1900 model for an expansion of the White House under the direction of Colonel Theodore Bingham, commissioner of public buildings.