The Life and Presidency of Calvin Coolidge

The White House Christmas Ornament 2015 Historical Essay

Copyright © White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

John Calvin Coolidge (he rapidly let go of "John") was born on the Fourth of July in 1872 to an old New England family. His father John Calvin Coolidge farmed in Windsor County, Vermont. The young Calvin lost his mother Victoria Josephine Moore to what may have been tuberculosis when he was twelve; when he was seventeen, his younger sister and only sibling, Abigail Grace, died from what was probably appendicitis. After graduating from Amherst College in 1895, Calvin Coolidge studied law through apprenticeships with two attorneys in Northampton, Massachusetts. Admitted to the bar in 1897, he began his own practice the next year and soon established himself as a conscientious, meticulous lawyer.

In 1905, his landlord introduced him to Grace Anna Goodhue, a 1902 graduate of the University of Vermont and a teacher at the Clarke School for the Deaf. "Having taught the deaf to hear," the taciturn Coolidge wryly observed to a friend, "Miss Goodhue might cause the mute to speak." Her wit and charm were to be powerful assets to Coolidge's political career. They married in 1905 and had two sons, John born in 1906 and Calvin born in 1908.

During the 1890s and early 1900s Coolidge efficiently rose through the ranks of the local and state Republican Party: serving on Northampton's council, as city solicitor, as clerk of courts for Hampshire County, and as a representative in the Massachusetts House and State Senate. Extraordinarily reserved for a politician, he won respect for his thoroughness, diligence, and fair-mindedness. He served as mayor of Northampton and in 1915 was elected lieutenant governor. A conservative Republican who believed in limited government and reduction of debt, Coolidge broke with some in his party and came out in favor of women's suffrage. In 1918 he was elected governor and supported some mildly progressive measures. He achieved national fame during the 1919 Boston police officers strike with his assertion: "There is no right to strike against the public safety by anyone, anywhere, any time." In the turbulent atmosphere of post-World War I America, many saw Coolidge as a symbol of law and order, and his stance during the strike contributed to his surprise selection by the Republican National Convention for vice president in 1920.

As vice president to President Warren G. Harding, Coolidge had little to do aside from presiding over the Senate, although the gracious Harding invited him to regularly attend cabinet meetings. The Coolidges kept an $8 a day suite in the Willard Hotel and dined out often. When asked why they attended so many social functions, Calvin Coolidge replied, "Got to eat somewhere." Within Washington amusing stories soon arose about the vice president's withdrawn nature; perhaps the most famous concerned a society matron who told Coolidge at a dinner party: "Mr. Vice President, I made a bet with my friends that I could get you to say at least three words this evening." Coolidge fixed a steely glare on her and said: "You lose." Alice Roosevelt Longworth observed of Coolidge: "When he wished he were elsewhere, he pursed his lips, folded his arms, and said nothing. He looked then precisely as though he had been weaned on a pickle." Yet comedian Will Rogers noted that Coolidge "had more subtle humor than almost any public man I ever met."

The Coolidge Administration (1923-1929)

The vice president was in Vermont visiting his father, far from telephones and electricity, when he received a telegram in the early morning of August 3, 1923, announcing President Harding's sudden death in San Francisco. As notary public was one of many local offices held by the elder Coolidge, the new president was able to promptly take the oath of office in his father's parlor at 2:47 a.m. by light of a kerosene lamp. He returned to Washington the following day.

On December 6, 1923 a presidential address was broadcast on a radio network for the first time as President Coolidge spoke to a joint session of Congress. The speech was heard by about half of the nation.

No two political figures could have been less alike than Coolidge and Harding. Yet Coolidge found in this an opportunity for a change in the tone of the presidency. Sensing the country wanted a breath of fresh air after the grandiloquent Harding years, Coolidge allowed his naturally quiet, thoughtful nature to be embellished into a persona of a leader who said and did no more than he had to. "The words of a president have an enormous weight," he wrote in his autobiography, "and ought not to be used indiscriminately." Through regular press conferences, photographs, and appearances on the radio and in talking motion pictures, Coolidge shrewdly cultivated a public image of a reticent, prudent Vermonter, and his reputation for integrity overwhelmed opponents' attempts to tie him to the emerging scandals that followed the Harding administration.

In 1924, Coolidge sought reelection with the slogan "Keep Cool with Coolidge" and won a tremendous victory with 54 percent of the vote in a three-way race, carrying 35 of the 48 states. Yet, whatever enjoyment Coolidge might have derived from winning a full term of his own was dissolved by the untimely death of his son Calvin Jr. on July 7, 1924. The 16 year old died of blood-poisoning, which developed from a blister on his foot, the result of playing tennis without socks. Coolidge wrote, "In his suffering [he] was asking me to make him well. I could not." The father, devastated, continued, "When he went the power and the glory of the Presidency went with him."

Coolidge believed that business and government should remain as separate as possible from one another with each in its own sphere, free of interference. His belief in limited, frugal government led him to veto legislation for farm relief and for development of electric water power in the Tennessee River Valley. His policies, marked by tax cuts, reductions in federal spending and minimal government regulation of private industry, banking and stock trading, were identified in the public mind with the remarkable, though unevenly distributed, economic prosperity of the 1920s. It spurred the tremendous growth of consumer products, especially automobiles and radios, thus significantly increasing mobility and access to developing news for many American families, especially those in rural areas.

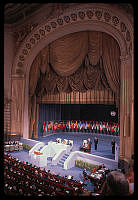

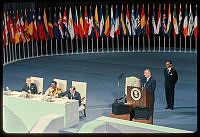

President Coolidge signed the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act and his Interior Department authorized the Brookings Institution to conduct exhaustive surveys of federal programs for Native Americans. Like Harding he encouraged vigorous Federal efforts to end lynching and backed U.S. membership in the World Court. Coolidge also favored Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg's plans to prohibit the use of war as an instrument of national policy, which resulted in the Kellogg Briand Pact of 1928. That same year Coolidge visited Havana and addressed a Pan-American conference of western hemisphere leaders. Issues with Mexico, Nicaragua, and China were mainly entrusted by Coolidge to his secretary of state and diplomatic personnel.

While vacationing in South Dakota's Black Hills in August 1927, Coolidge told the press, "I do not choose to run for president in 1928." During this two-month western trip, Coolidge received and accepted an invitation to dedicate the Mount Rushmore National Memorial.

Calvin Coolidge enjoyed wearing a cowboy hat and Western garb while on a 2-month vacation in the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1927.

Over the next 14 years sculptor Gutzon Borglum directed the carvings of the likenesses of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt. In March 1929, Coolidge left the White House to his successor Herbert Hoover and returned to Northampton for retirement. Coolidge busied himself with writing magazine articles, a regular newspaper column, and his autobiography. Even as the stock market crash of October 1929 led to a worldwide depression, Coolidge remained so popular that some Republicans wished to nominate him instead of Herbert Hoover in 1932. Coolidge, however, knew that his days in public life were over; as he put it: "We are in a new era to which I do not belong, and it would not be possible for me to adjust to it." Less than a month later, on January 5, 1933, he died of a heart attack at age 60.

White House Improvements

During the Coolidge administration, the most conspicuous change to the White House was the replacement of the surviving 1817 attic with a full third floor. President Coolidge, when told of the structural difficulties of the attic, asked that if it was in such crisis, "why doesn't it fall down?" In 1927 William Adams Delano of the New York firm of Delano Aldrich was called upon for design advice. After studying James Hoban's 1793 drawing, Delano increased the pitch of the roof and lowered the floor to accommodate new guest and service rooms beneath a new steel and concrete roof structure. At Mrs. Coolidge's request, a rooftop sunroom facing south toward the river was added. The "Sky Parlor," as it was originally called after attic rooms in old Virginia houses, has descended through time as the "Solarium." The Coolidges' Third Floor survived President Harry Truman's 195052 renovation of the house.

Grace Coolidge, keenly interested in history and disappointed to find few original furnishings on her arrival at the White House, began to study old photographs of the State Floor. In 1925 the first lady obtained a Congressional resolution for the acceptance of treasured objects as gifts to a permanent White House collection and secured the assistance of an advisory committee of experts to evaluate and make recommendations on the dcor of State Rooms and to review the offers of gifts. Plans were proposed by the committee to refurnish the Green and Red Rooms in a Colonial Revival style, but the proposals created so much public controversy that President Coolidge spiked them. Mrs. Coolidge crocheted a coverlet for the "Lincoln Bed" with the intent of starting a tradition where each first lady would leave a memento of life in the White House.

Coolidge Christmas Celebrations

The Coolidges celebrated their first Christmas in the White House in 1923 quietly, with their sons Calvin Jr. and John, who were both home from Mercersburg Academy in Pennsylvania. At 5:00 p.m. on Christmas Eve the president pressed a button and lighted strings of more than 2,500 electric bulbs on the National Christmas Tree, a 60-foot tall fir from his native Vermont given by Middlebury College, on the Ellipse. More than 6,000 people then arrived on the White House grounds at the Coolidges' invitation to sing Christmas carols with the choir of the First Congregational Church, and enjoy the music of the U.S. Marine Band. President Coolidge became the first chief executive to preside over a public celebration of the Christmas holidays. Since 1954, the Christmas Pageant of Peace has been held annually on the Ellipse and includes the lighting of the National Christmas Tree and respects the holiday worship of all faiths.

Mrs. Coolidge spent Christmas day in 1923 helping the Salvation Army distribute food baskets. After Christmas dinner, the entire Coolidge family went to Walter Reed Hospital where they joined several hundred disabled veterans for a preview of the motion picture Abraham Lincoln produced by Al and Ray Rockett. For the Coolidges, their sorrowful Christmas of 1924 was preoccupied with memories of their younger son Calvin Jr. Despite the tragedy, the Coolidges maintained the ceremonial lighting of the National Community Christmas tree followed by a performance by the president's First Congregational Church choir singing carols at the White House. The first lady continued her support of the Salvation Army and the Union Mission by distributing food baskets and toys to families in need. Throughout the Coolidge administration, Christmas celebrations were a mix of traditional family gatherings and the new community centered public ceremony symbolized by the lighting of the National Christmas Tree.

President Coolidge was the first president to participate in a public celebration of the Christmas holiday turning on the switch for the "National Tree Lighting" in President's Park. December 24, 1923.

Library of Congress