Rubenstein Center Scholarship

"Running Against the World"

Jesse Owens and the 1936 Berlin Olympics

“I wasn’t running against Hitler. I was running against the world.”

-Jesse Owens

Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics

Library of CongressThe 1936 Summer Olympics were unlike any other. In Berlin, Germany, under the shadow of Chancellor Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime, an African-American track and field athlete rose to stardom: Jesse Owens.1 Owens’s record-breaking athleticism carried him from the cotton fields of the South to the White House and made him one of the most famous athletes in American history.

James Cleveland “Jesse” Owens, the descendent of enslaved laborers and son of sharecroppers, was born in Oakville, Alabama in 1913. Like many Black Americans around the turn of the twentieth century, his family left the South in search of new opportunities as part of the Great Migration, eventually relocating to Ohio.2 As a young man, Owens began running for sport and joined his middle and high school track and field teams in Cleveland.3 His exceptional athletic talent became evident during his senior year of high school, when Owens broke the world record for the 220-yard dash and tied the record for the 100-yard dash.4

The Ohio State University recruited Jesse Owens in 1933 and he continued to shatter records on the university’s track and field team.5 Despite his extraordinary talent and ability, he, like many Black Americans, continued to face Jim Crow-era segregation and discrimination. At Ohio State, Jesse could not live in the same dormitories or eat in the same restaurants as his white teammates.6

Owens at The Ohio State University, 1934

The Ohio State University Archives, Jesse Owens Photograph CollectionNevertheless, Jesse’s skill as an athlete soon made him a household name. In July 1936, Jesse Owens competed at the U.S. Olympic Trials in New York City and dominated the track and field contests, securing a spot on the U.S. Olympic Team. American participation in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, Germany had been the subject of controversy since Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. Citing Nazi Germany’s dictatorial, discriminatory actions and explicit anti-Semitism, a number of prominent Americans proposed a boycott of the event, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as religious organizations across the country.7 Some individual athletes, including Jewish hurdler Milton Green, personally boycotted the event.8 In the same vein, NAACP Secretary Walter White hoped that Jesse Owens and other Black athletes would join the boycott, writing:

Participation by American athletes, and especially by those of our own race which has suffered more than any other from American race hatred, would, I firmly believe, do irreparable harm…If the Hitlers and Mussolinis of the world are successful it is inevitable that dictatorships based on prejudice will spread throughout the world…9

Owens originally expressed reluctance to participate, but like many Black athletes, he saw the Olympic Games as an opportunity to prove himself on the world stage and to discredit ideas of racial inferiority in the United States.10

Notably silent in these conversations was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who avoided involvement with issues related to a boycott of the Olympic Games.11 In the end, an American boycott did not garner adequate support and the United States sent 312 athletes, including Jesse Owens and seventeen other African Americans, to compete in Berlin.12

Adolf Hitler deliberately designed the Berlin Olympics to emphasize German strength and to support his and his regime’s belief in the supremacy of the Aryan race—but Jesse Owens had other plans. During the first week of August 1936, Owens triumphed against his competitors, breaking multiple world records and earning four gold medals in track and field for the 100-meter sprint, the 200-meter sprint, long jump, and the 4 x 100-meter relay.

Owens stands on the podium after winning a gold medal at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

National Archives and Records AdministrationAlthough Germany won the most overall medals that summer, architect and Nazi minister Albert Speer later recollected that Hitler “was highly annoyed by the series of triumphs by the marvelous colored American runner, Jesse Owens.”13 Many American newspapers published stories claiming that Hitler slighted Owens at the Olympic Games by not shaking his hand, when in fact, Hitler did not shake hands with any American medalists; according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum: “during the very first day of Olympic competition…. Olympic protocol officers implored Hitler to receive either all the medal winners or none, and Hitler chose the latter.”14

After the Olympics, Owens returned home a champion. Ticker tape parades and ceremonies celebrated his success in Berlin, but he was still treated unfairly because of his skin color. Owens lamented that “I came back to my native country and couldn’t ride in the front of the bus…I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted…I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the president either.”15 Archival documentation shows that Americans urged Roosevelt to welcome the track and field star at the White House, but that the president did not invite any athletes, regardless of race, to celebrate at the Executive Mansion. One letter addressed to the president reads:

I am writing today to ask that you make provision for the successful contestants of the Olympic games in Germany to be officially received by yourself upon their return home without regard to race or color. I am certain that you are not aware of the electric effect such an action on your part will have upon the twelve million Negroes in America…16

Owens at a ticker tape parade held in his honor in New York City

The Ohio State University Archives, Jesse Owens Photograph CollectionUnfortunately, President Roosevelt did not receive or contact Jesse Owens, who later commented: “Hitler didn’t snub me—it was our president who snubbed me…The president didn’t even send me a telegram.”17 Ironically, Owens defeated racism on the world stage but could not escape it at home.

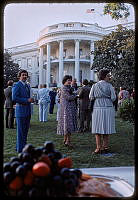

A number of other presidents and first ladies honored Owens during and after his lifetime, and the track and field star remained in the public eye long after his retirement from amateur sports in 1936. In 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower named Owens “Ambassador of Sports,” and asked him to represent the United States at the 1956 Olympics; Owens also traveled to Asia on behalf of the nation during the Cold War as a goodwill ambassador.18 In 1972, he was welcomed to the White House by First Lady Patricia Nixon in celebration of the annual Cherry Blossom Festival.19 Meanwhile, Owens raised three daughters with his high school sweetheart, Ruth.

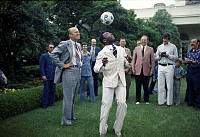

In a White House ceremony held in the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden on August 5, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford awarded the star athlete the highest civilian honor possible: The Presidential Medal of Freedom. The citation read:

To Jesse Owens, athlete, humanitarian, speaker, author -- a master of the spirit as well as the mechanics of sport. He is a winner who knows that winning is not everything. He has shared with others his courage, his dedication to the highest ideals of sportsmanship. His achievements have shown us all the promise of America and his faith in America has inspired countless others to do their best for themselves and for their country.20

President Ford presents Jesse Owens with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 1976

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum/NARAOwens stood before the crowd that day and emphasized:

I don't care where anybody lives, I don't care what they do, because you can be born into anything in this Nation, as I was born in the cottonfields of Alabama, and today I stand before you and shake hands with the Commander-in-Chief of our Nation.21

Jesse Owens returned to the White House in 1979 to receive a Living Legacy Award from President Jimmy Carter. Carter spoke before a crowd of honorees, recognizing: “a young man who possibly didn’t even realize the superb nature of his own capabilities went to the Olympics and performed in a way that I don’t believe has ever been equaled since.”22 Jesse Owens died a year later from lung cancer on March 31, 1980. He posthumously received the Congressional Medal of Honor from President George H.W. Bush in 1990.23

Jesse Owens meets President Jimmy Carter at the Living Legacy Awards.

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library/NARAWhen President Barack Obama welcomed athletes to the White House after the Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 2016, he invited an additional group of athletes—the families of Jesse Owens and his fellow Black Olympians. Gathering in the East Room, President Obama praised the athleticism and perseverance of the eighteen Black Americans who competed in 1936, stressing: “It was… African-American athletes in the middle of Nazi Germany under the gaze of Adolf Hitler that put a lie to notions of racial superiority — whooped 'em and taught them a thing or two about democracy and taught them a thing or two about the American character.”24