Photographs of Indian Delegates in the President's "Summer House"

Copyright © Spring 2009 White House Historical Association. All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this article may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Requests for reprint permissions should be addressed to books@whha.org

In the early spring of 1863 a delegation of Southern Plains Indians, members of the Apache, Arapaho, Caddo, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa tribes, were invited to Washington to meet with President Abraham Lincoln at the height of the Civil War. The purpose of the visit was to secure peaceful relations with the Indians and to dissuade them from joining forces with the Confederacy. Recruitment of Native Americans to fight for the South had met with some success, notably among the Cherokee Nation in the Trans-Mississippi West, and overtures were being made to other tribes in the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. The Indian delegation accompanied by their agent, Samuel G. Colley, and their interpreter, John Simpson Smith, were escorted into the East Room of the White House, where they were immediately confronted by a large assembly of gentlemen and ladies including foreign ministers and their families, secretaries of the interior, state and treasury, the commissioner of Indian affairs, and a host of distinguished guests. According to newspaper accounts, “The savages were dressed in full feather—buffalo robes, Indian tanned, and bead worked leggings, with a profusion of paints upon their faces and hair, etc. . . . They squatted themselves down upon the floor in a semicircle—fourteen chiefs and two squaws—and were instantly surrounded by the curious crowd.”1 One of the delegates, a Kiowa chief named Yellow Wolf, drew special attention for the large silver peace medal he wore, given to the Kiowas by President Thomas Jefferson. The medal had been handed down for generations and was held in the highest esteem by the tribe.2

After a brief wait President Lincoln entered the room and listened attentively to introductory remarks by Superintendent of Indian Affairs William P. Dole. Then the interpreter, John Smith, introduced each of the chiefs to the president, who solemnly shook their hands. The president, speaking to the Indians through their interpreter, told the chiefs that he was eager to hear anything they wished to say. Two Cheyenne chiefs, Lean Bear and Spotted Wolf, each addressed the president with expressions of amazement for all the wonderful things they had witnessed; they pledged their tribal friendship but expressed dire concern about the encroachment of white settlers on their lands. President Lincoln responded by telling the Indians that “It is the object of this Government to be on terms of peace with you and all our red brethren. We constantly endeavor to be so. We make treaties with you, and will try to observe them” Lincoln continued, “The palefaced people are numerous and prosperous because they cultivate the earth, produce bread, and depend upon the products of the earth rather than wild game for a subsistence. This is the chief reason of the difference; but there is another. Although we are now engaged in a great war between one another, we are not, as a race, so much disposed to fight and kill one another as our red brethren.”3 The bitter irony of telling the chiefs of the Southern Plains that the white race was not as warlike as the Indians were inclined was not lost on the crowd of guests who were painfully aware of the enormous carnage of the ongoing Civil War. Lincoln then concluded the meetings by telling the chiefs that the commissioner of Indian affairs would see that the delegation would soon be returned home. The president rose and once again shook hands with each of the chiefs. Later that afternoon the delegation was ushered to the west end of the White House and crossed the path to the Conservatory, where one of Mathew Brady’s cameramen was busily preparing to take group portraits.

The Lincoln White House Conservatory, also known as the greenhouse or “President’s Summer House,” was actually the second building used for the purpose of botanical retreat. The first stood on the east side of the mansion near the old stable. Both decrepit structures were torn down to make way for the Treasury Building extension. The inception of a new White House Conservatory began with President Franklin Pierce, but actual construction of the building did not start until President James Buchanan assumed office. Located just 12 feet west of the White House and connected by a narrow glazed passage, the large wooden structure was completed in 1857 at a cost of $16,000. “The glass roof and sides made it seem light, despite its mass . . . Inside, the conservatory had one grand central room, very high and with a steeply slanted ceiling; it housed rows of heavy, green-painted tables. On them plants en mass created a thick growth of greenery and bloom.”4 President Lincoln’s personal secretary, George Nicolay, attended the meeting with the Southern Plains Peace Delegation at the White House and after the adjournment accompanied the visitors to the Conservatory. A few weeks later Nicolay wrote to his future wife, Therena Bates, a firsthand account of the event:

Executive Mansion, Washington, April 9, 1863.

Dear Therena

I am still enjoying the quiet in the house produced by the President’s absence. He has not yet returned from Fredericksburg, or rather Falmouth, and consequently the crowd that usually haunts the interchamber and my office keep at a distance. He will probably be back again by tomorrow, when they will once more swarm in upon us like Egyptian locusts.

I enclose you a little picture of a group taken about two weeks ago, in our conservatory here. A delegation of Indians from the plains were here to see the President, and afterwards they were taken out into the greenhouse and photographed as you see them, original copperheads5 against a background of palefaces. The young ladies are, counting from the left, Miss Geralt, Miss Lisbon,6 Miss Kennedy, and another Miss Geralt, all but Miss Kennedy belonging to the Diplomatic Corps. I have a stereoscopic view of it which shows to better advantage.

Your George.7

The “little picture” which Nicolay included in his letter is preserved in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, an unmounted albumen carte de visite—size photograph—approximately 2 by 3H inches. The carte de visite or visiting card photograph was a favorite format for paper photographs taken during the Civil War. Nicolay further stated that he had a stereoscopic view of the group portrait, referring to the popular mid-nineteenth-century double-image card that, when seen through a stereoscopic viewing device, produced a three-dimensional picture.8

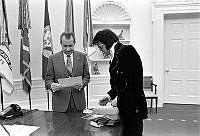

Mathew Brady, the noted Civil War photographer, produced three distinct views of the Indian delegation taken in the White House conservatory. In each of the three photographs the most influential members of the Southern Plains Delegation were prominently posed in the front row. Three Cheyenne chiefs—Standing in Water, War Bonnet, and Lean Bear were seated next to the Kiowa leader, Yellow Wolf. In two of the photographs Yellow Wolf’s Jefferson Peace Medal is plainly visible. The two front rows of Indians and their interpreter remained for all three photographs, creating a setting for the other visitors to be included in the historic record.

Two of the three Brady negatives for the Indian photographs were numbered and published as stereoviews by E. & H. T. Anthony, New York City. One image (not published as a stereoview) includes Kate Chase, the vivacious daughter of Secretary of the NOTES Treasury Salmon P. Chase, standing next to three gentlemen—the interpreter John Smith and two unidentified guests. To the right of Miss Chase are three women whose identities remain unknown but may have been family members of visiting dignitaries. Another group portrait portrays only Native Americans with their interpreter, John Smith. In the third conservatory portrait George Nicolay is positioned at center in the back row, flanked by four identified family members of the diplomatic corps. At the far left of the image in the back row stand John Smith and Indian agent, Samuel G. Colley. The enigmatic bonneted woman in the back row, far right, has sometimes been referred to as First Lady Mary Lincoln. No contemporary identification, however, supports the claim, and even George Nicolay who named all the other non-Indian guests in the picture, failed to provide her identity.9

Just eight days after Yellow Wolf visited the White House, he died of pneumonia at his Washington hotel. His personal effects—bow and arrows, buffalo robes and blankets, and the large silver peace medal, a present from President Jefferson to Yellow Wolf’s ancestors, were buried with the Kiowa chief in a government-furnished coffin. Yellow Wolf was laid to rest far from his native Plains in Congressional Cemetery.10 The fates of the three Cheyenne chiefs photographed next to Yellow Wolf are equally sad. Less than two years after their peace mission to Washington, all three chiefs were killed. War Bonnet and Standing in Water were slaughtered in the Sand Creek Massacre. Lean Bear was mistaken for a hostile and killed in May 1864 by Colorado troops intent on following orders to shoot Indians wherever they were found on the Plains.

The peace medal given to Lean Bear during his visit to the White House was found on his bullet-riddled body and in his hand was clutched a piece of paper verifying that he was a peaceful friend of the whites— signed, A. Lincoln.11

Interpreter John Smith and the six Indian men and two women who posed in the group portrait with Nicolay appear again with a new set of visitors to the White House Conservatory. Standing in the back row at left are two unidentified gentlemen. The young woman to their right is Kate Chase, the charming daughter of Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. The three other women remain unidentified, though they are no doubt family members of visiting diplomats. The large silver peace medal given by President Thomas Jefferson to the Kiowas is visible around the neck of Yellow Wolf, seated in the first row at far right.

Picture History

The subjects seated in the front row, left to right, have been identified as Standing in Water, War Bonnet, and Lean Bear, Cheyenne; and Yellow Wolf, Kiowa. In the middle row at left is the Kiowa woman, Coy, beside her husband, White Bull. An unidentified white child stands among the Indians. To the viewing right of the child is Lone Wolf, a Kiowa, and Etta, wife of Little Heart. The gentlemen standing at left in the back row are John Simpson Smith, interpreter and Samuel G. Colley, Indian agent. Standing next to Colley are Miss Geralt and Miss Lisbon. The tall figure at center is Lincoln’s personal secretary, 31-year-old, John George Nicolay. To the viewing right of Nicolay are Miss Kennedy and another Miss Geralt. The four women and the white child were probably family members of visiting diplomats. The bonneted woman at far right has occasionally been identified as Mary Lincoln, but positive identification remains unresolved. Less than two years after this photograph was taken all four of the Indian peace delegates seated in the front row were dead. Yellow Wolf succumbed to pneumonia days later and was buried with his Jefferson Peace Medal in Congressional Cemetery. The noncombatant Cheyennes, War Bonnet and Standing in Water, were slaughtered by Colorado Territory Militia in the Sand Creek Massacre on November 29, 1864. On May 16, 1864, mistaken for a hostile, Lean Bear protested that he had “visited the home of the White father” but fell under a volley from the same militia. Brady negative number 2735, published as a stereoview by E. & H. T. Anthony, New York.