Rubenstein Center Scholarship

Jerry Smith

White House Duster

Jeremiah “Jerry” Smith worked at the White House through eight presidencies. Government documents listed him as a laborer, but he took on a variety of unofficial roles, including valet, footman, custodian, and most notably, duster. Throughout his thirty-year tenure, Jerry witnessed three White House weddings, the aftermath of two assassinations, the installation of electricity, the construction of the West Wing, and the addition of telephones and typewriters in the White House.1 Most importantly, he developed close relationships with presidents, first ladies, first children, and co-workers, leaving an indelible mark on the White House in the late nineteenth century.

Callers at the White House came to know Jerry, always dressed in white linen suit, and Turkish cap, and holding his signature feather duster.

Library of CongressJeremiah Smith was born in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, circa 1839/1840.2 He served in the Union Army as a teamster and sailor during the Civil War, and relocated to Washington, D.C. afterwards.3 In 1870, he married seamstress Sarah Elizabeth Jackson and they had nine children together.4

Sometime around 1873, he joined President Ulysses S. Grant’s White House staff.5 Jerry later shared the story of his arrival in a 1903 Washington Post interview:

I…met Gen. Grant once on board a ship when he was coming with his family from Boston to Fort Monroe. Afterward, I waited on him at the big banquet given him at the Barnum Hotel in Baltimore, and it was here that he told me to call on him at the White House. I did, and was set to work about the grounds.6

Smith became close with the Grant family during their time in the White House, filling a variety of positions including footman, waiter, and housekeeper.7 He also acted as a valet to President Grant, telling reporters “I used to wait on him all the time, brush his clothes, and go with him on his trips.”8 In 1874, he witnessed the wedding of First Daughter Nellie Grant and Algernon Sartoris.9 At the conclusion of Grant’s second term in 1877, he asked Jerry to leave the White House with him, but instead, Jerry stayed—for a quarter of a century.10

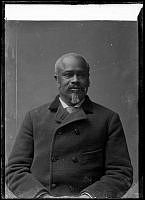

Jerry Smith is photographed here by C.M. Bell, date unknown.

Library of CongressWhen President Rutherford B. Hayes and First Lady Lucy Hayes arrived, they assigned him to cleaning duty, and over the next several years, reporters referred to him as the “White House duster.”11 Many years later Jerry recalled that Mrs. Hayes “would not let none of us use any wine and made all of us servants go to church every Sunday.”12

Jerry served through James Garfield’s short tenure as president, earning $720 per year for his services.13 After Garfield was shot by assassin Charles Guiteau on July 2, 1881, Smith recollected, “I used to bring him in his beef tea every morning, and when I would ask him how he felt, he would smile and say ‘Pretty well, Jerry, for a man who has been shot.’”14 Unfortunately, Garfield did not recover from his wounds, passing away on September 19, 1881.

Jerry’s work at the White House continued no matter who was in office. Under Chester Arthur, Jerry continued to work as a laborer, dining room servant, and custodian.15 Smith called Arthur “the finest gentleman that was ever in the White House” telling newspapers that he was “kind and considerate and all liked him.”16 President Grover Cleveland and First Lady Frances Cleveland left such a mark on Jerry that he almost named his daughter Frances—although his wife objected.17 The affection was mutual—the Fort Scott Weekly Tribune reported “Mrs. Cleveland is very fond of him, partly because of his usefulness and partly on account of his laugh…Whenever Mrs. Cleveland was attacked with the blues, which was not often, she contrived to get Jerry to laugh, for he has a laugh that drives full care away.”18

Under President Benjamin Harrison and First Lady Caroline Harrison, he continued to be a jack-of-all-trades. On one occasion, a constituent sent two possums, named “Mr. Protection” and “Mr. Reciprocity,” to President Harrison.19 Upon their delivery, Jerry managed the critters. According to newspapers, “for several weeks [they] were his special pets, as he watched them grow fatter day by day, as they drew nearer the presidential palate (sp.).”20 The press subsequently nicknamed him “Possum Jerry” and “Keeper of the Royal Possums.”21

The Fort Worth Daily Gazette included this sketch of Jerry Smith and First Lady Caroline Harrison in an 1890 article, writing “Old Uncle Jerry, who has been in the White House for a quarter of a century, always gets a kindly ‘Good morning Jerry,’ from Mrs. Harrison…[he says] cheerfully, ‘Mawnin’ Mrs. Harrison’.”

Fort Worth Daily GazetteAlthough Smith called the Harrisons “mighty pleasant,” he was particularly glad to see the Clevelands return to the White House in 1893.22 Long-time employee Colonel William H. Crook wrote:

When Mr. and Mrs. Cleveland came back to the White House, Jerry did not seem at all surprised. He seemed to think their return was predestined by some power higher than we mortals…Jerry was superstitious in many things, but in placing Mrs. Cleveland far above the average of humanity, he showed not superstition but common sense.23

Jerry Smith was indeed superstitious—he claimed that he saw the spirits of former presidents wandering throughout the halls of the White House. His first ghostly encounter was President Abraham Lincoln, whom he professed to see “hundreds of times…always gliding silently about the stairs and rooms and always with a sad, serious expression on his face.”24 Then, following the death of Ulysses S. Grant in 1885, Smith contended that he saw the apparition of his former boss and told newspapers that Grant’s ghost frequently spoke to him.25

This newspaper illustration depicts Jerry Smith's ghostly encounters at the White House.

Salt Lake HeraldIn addition to specters, Jerry witnessed several major events at the White House throughout his decades there, including State Dinners, parties, Inaugurations, and weddings—but first families also contributed to his special moments. On March 30, 1895, Jerry and his wife Sarah celebrated their silver wedding anniversary with a party at their home in Brightwood near Rock Creek Park. Although the Clevelands were unable to attend, they gifted the happy couple a dozen silver spoons. Secretary of War Daniel Lamont and his wife, Juliet, attended, as well as Postmaster General Wilson Bissell, Secretary of the Treasury John Carlisle, and Henry T. Thurber, the president’s private secretary.26 Former First Lady Julia Grant and her daughter, Nellie Grant Sartoris, also sent silver cutlery and their well-wishes.27 This special evening indicates the close relationship shared by members of first families and Jerry.

It is no surprise that Jerry had so many well-wishers. By 1895, Jerry was a veteran employee, known by Washington’s elite and frequently mentioned in the press. As one newspaper wrote, “Many ladies in this city esteem an obesance (sp.) from Uncle Jerry in public more than a lift of the hat from the President himself.”28 He charmed the masses with his genteel manners, which earned him the nickname “Lord Chesterfield,” and delighted employees and first families alike by singing and humming while he worked.29

After the Clevelands departed—this time for good—in 1897, Jerry worked for President William McKinley and First Lady Ida McKinley. He told reporters that she was “just as nice to a colored person as she is to a white—it don’t make no difference what your color is, she is always the kind lady.”30 Despite his age, Jerry was an indispensable member of the staff. The Evening Star wrote that “Jerry is the hardest-worked man on the White House pay roll. He has to do a little of everything, but his chief work is in keeping the dirt and dust out of sight.”31

On September 6, 1901, while cleaning in the Telegraph Room, Jerry heard tragic news over the wire—President McKinley had been shot while visiting the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. He quickly informed White House Doorkeeper Thomas Pendel and his other co-workers.32 After his assassination in 1901, William McKinley joined the cohort of ghosts that Smith reportedly encountered about the White House.33 34

Doorkeeper Thomas Pendel and Jerry Smith worked together at the White House for decades. Newspapers noted, “they know things about that historic place that others do not dream about.”

Theodore Roosevelt was the last president to employ Jerry Smith. By 1901, Jerry had served in the White House for decades, and the house was much different than it had been in the 1870s. In 1902, Roosevelt oversaw the renovation of the White House and the construction of the Temporary Executive Office, later known as the West Wing. This addition of new office space was beneficial for the president and his staff, but it had an adverse effect on Jerry. According to him, the new buildings chased out the ghosts! Jerry told reporters, “They done tore the White House up an’ spirits ain’t comin’ hangin’ round any new places.”35 He was sorry to see his old friends go.

By Roosevelt’s administration, Jerry was in his sixties. He experienced rheumatism and vision loss, which began to impact his work.36 For example, in addition to his dusting duties, Jerry raised and lowered the American flag atop the White House at sunrise and sunset.37 He took great pride in these duties, “regarding the ceremony as being particularly important, and in a way symbolical of his own religious and patriotic feelings, which were very closely merged.”38 In 1903, due to his nearsightedness, he accidentally hoisted the flag upside-down, which is a signal for distress or danger. As a result, Roosevelt relieved Jerry of the responsibility, passing it to the Navy Department.39 Shortly after this incident, Jerry retired on pension from his role at the White House in December 1903.40

“If anybody tried to discharge him, he simply wouldn’t be discharged. Luckily, nobody will try it.” - York Daily Record, August 17, 1903.

During the summer of 1904, Jerry’s health worsened, and President Roosevelt personally called on him at his Brightwood home.41 Newspapers reported that “Jerry was greatly cheered by this visit, and his physicians say this encouraged him to hold on to life a little longer.”42 Jerry Smith passed away at his home on July 25, 1904. Many White House employees attended the funeral, held at the Metropolitan A.M.E. Church, and President Roosevelt sent a floral emblem of the White House to adorn Jerry’s coffin.43 He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery.

Jerry’s retirement marked the end of an era. For the first time in thirty years, presidential callers encountered a White House without Jerry Smith’s charming smile and sense of humor. Presidents temporarily worked at the White House, but Uncle Jerry was a White House fixture.